The Tale of Beatrix Potter

Nancy Alsop looks back on how Beatrix Potter’s “little books” were shaped by the landscape of the Lake District, which redeemed her life after it was hit by tragedy…

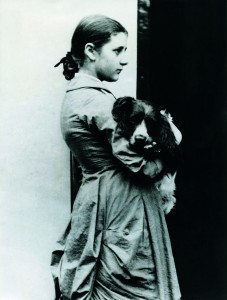

“Thank goodness I was never sent to school; it would have rubbed off some of the originality.” It is fortunate then that Helen Beatrix Potter was born on 28 July, 1866, when it was customary for young Victorian women to be educated within the confines of their home, rather than via the rigours of school.

For Potter, who grew up in Kensington, London, the daughter of a wealthy lawyer, Rupert Potter, and his wife, Helen Leech, education came courtesy of governesses; breaking with the cliché of the primly buttoned-up school ma’am-ish Victorian, the home schoolroom would prove formative for Potter, largely thanks to one Annie Carter. Charged with imparting wisdom and learning, she was only three years older than Potter and the two remained lifelong friends; it was this one-time tutor who gently encouraged her protégé throughout her life, nudging her to turn what started as charming illustrated letters to Carter’s (later Moore) children into a book. Indeed, one letter to Noel, her eldest and often sickly child, told a story of “four little rabbits whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter”. That letter became the basis of Potter’s career.

Long before that, Moore had allowed Potter and her brother Bertram to keep a small menagerie of pets in the schoolroom (mice, rabbits and hedgehogs all featured), who were both company and inspiration. The early care, observation and sketching of the creatures in Potter’s custody would fuel her imagination for life. Carter also filled her young charges’ heads with tales of witches, fairies and legends, encouraging them to read, which Potter did, voraciously (her keen appreciation of writers such as Edward Lear found a voice in her own relished use of words such as “lippity, lippity”). All of which did much for material-gathering for Potter’s own books; but little to make her more acceptable to her mother, who openly regretted that she had not raised a daughter given more to London’s social whirl than quietly rebelling with her study of fungi, toadstools and wild creatures.

But while the schoolroom sparked the fire of imagination, the embers would be stoked by the countryside – and, more specifically, by the Lake District, north-west England. “My brother and I were born in London because my father was a lawyer there. But our descent, our interests and our joy was in the North Country,” she once explained. In her youth, the Potters would decamp to the Lakes for holidays, where Beatrix would leap upon the opportunity to study the nuances of British wildlife, eagerly making sketch studies of its abundant flora and fauna (it was also from the Lakes and Scotland that she would typically send the illustrated missives that would eventually lead to her becoming a published author).

Those northern sojourns did more than simply elicit charming sketches; her observations led to publishing scientific illustrations and, in 1896, she even penned her own paper titled On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae. But it was not until 1905, by then the beloved author of a tale of a disobedient rabbit named Peter, The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1901), that she laid down roots in the Lake District, a move propelled by personal tragedy. It was also a move that would change her life.

A published author

In the preceding years, Beatrix Potter, encouraged by Annie Carter, had touted her “little books” as she called them (she insisted they be the right size for little hands and not too expensive either) around London publishers. In their folly, all but one turned her down. But that solitary yes, on the proviso that she produce colour rather than black-and-white illustrations, proved a professionally and personally fruitful alliance.

Frederick Warne & Co eventually took the 36-year-old Potter’s charming bait. Despite first rejecting her offerings, they subsequently recognised the market for her books, duly sending the youngest of the dynasty – Norman Warne – to negotiate with Miss Potter. Theirs was a productive editor-author partnership, and together they agreed every detail of The Tale of Peter Rabbit. She said: “I hope the little book will be a success [as] there seems to be a great deal of trouble being taken with it.” The result? The first print run sold out before publication and by 1905 the duo had published: The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin; The Tailor of Gloucester, The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, and The Tale of Two Bad Mice.

A less expected result? The spinster of whom Potter’s mother had despaired was in love and engaged. Her parents’ horror and their refusal to allow their daughter to marry into trade made scant difference to a quietly defiant Beatrix, who accepted. Tragically, though, no marriage would ever take place. Warne died suddenly of leukemia a month later.

Life in the Lakes

His legacy remained in evidence throughout Potter’s life. The pair had discussed buying a cottage in the Lake District and, duly, the bereaved author’s first decision was to buy Hill Top, her now National Trust-run 17th-century farmhouse in the Cumbria village of Sawrey, purchased with proceeds from her “little books”. After all, without Warne, they may have remained a private pleasure.

While Potter didn’t live full-time in the Lake District, it became a symbol of her independence in the face of having to resume life as an unmarried daughter. It also acted as an inspiration for her work; just as an earlier holiday spent at Fawe Park at Derwentwater had supplied the blueprint for Mr McGregor’s garden in The Tale of Peter Rabbit, so her new home provided the model for the farmhouse in The Tale of Samuel Whiskers and The Tale of Tom Kitten. Her fantasy of a bucolic life found expression through the home she created, the dream emanating ultimately from her own imagination; each room was a stage set upon which the stories could play out (the oak dresser in the kitchen, for example, features in The Tale of Samuel Whiskers). But, above all, it was at the Lakes, resplendent with mists and snow in the winter, that she could allow her grief to manifest. As she said: “Somehow winter seems more appropriate to the sad times, than the glorious summer weather.”

Happily, neither the Lakes nor Hill Top were destined to forever remain places in which to explore the depths of her sorrow. Even without her beloved editor, the little books’ success continued apace. However, animals and nature remained her favoured company, so not for Potter and her fortune the social whirl of London. Instead, she expanded her life in the Lakes, buying numerous fell farms and breeding Herdwick sheep (a threatened breed native to the area), in the process meeting William Heelis, a Westmorland solicitor who managed the deals on the extensive property she bought in the area. The pair bonded over their mutual love of the Lake District and, at 47, in October 1913, Beatrix Potter married, her Jane Austen ending a reality at last. After that, her literary output declined (along with her eyesight), overtaken by her obsession with cultivating and preserving the land that had given her so much.

Beatrix Potter’s association with Cumbria and its lakes endures today. Her early sojourns in the area shaped the books that have charmed millions, while her legacy has been to preserve that glorious county as she left it. Schooled in the care of the environment as a teenager by Lake District vicar Hardwicke Rawnsley, she supported him for life, not least when he went on to become a founder of the National Trust. She fastidiously followed its guidelines for land maintenance and farming and, vitally, left her 4,000 acres, 14 farms and 20 houses to the Trust, as well as Hill Top – all thanks to the money earned by Jemima, Peter, Mrs Tiggywinkle and friends. It was a fitting bequeathal, designed to preserve the place she’d been happiest; the image of a tweed-clad Potter searching for errant sheep and winning prizes for her livestock is not as enduring as that of the young illustrator, but it was the role in which she was most contented.

Beatrix Potter died in 1943. Even as she grew frail, she rejoiced that she was able to call on the details of her beloved Lake District: “Thank God I have the seeing eye… as I lie in bed I can walk step by step on the fells and rough land seeing every stone and flower and patch of bog and cotton pass where my old legs will never take me again.”