Mary Shelley and her monster

Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein while she was still a teenager. Two centuries on, Nicola Rayner explores the troubled gestation of this landmark British novel

When Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, died in 1851, a worrying rewriting of history began that continued for decades. A trend appeared in the obituaries of the time: “It is not… as the authoress even of Frankenstein… that she derives her most enduring and endearing title to our affection,” ran a piece in The Literary Gazette, “but as the faithful and devoted wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley.”

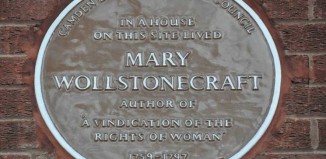

Others followed suit, focusing on her roles as wife of the famous poet and daughter of the renowned radicals William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. The latter, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, had died of puerperal fever 11 days after giving birth to Mary in a tragedy that would colour her daughter’s life for ever. But Mary Shelley was extraordinary in her own right and one need look no further than her Gothic masterpiece Frankenstein to understand that. Published 200 years ago, in 1818, it still has an astonishing power – and Mary wrote it when she was barely 19 years old.

Writing Frankenstein

Often called the first true work of science fiction, the novel tells the story of scientist Victor Frankenstein and the most famous experiment-gone-wrong in literary history. One of those words that has migrated from its original meaning, “Frankenstein” has been used so often to refer to the scientist’s vengeful creature, as well as the man himself, that it is almost acceptable. It is a neat but accidental reflection of the way the fates of the two – creator and created – are inextricably intertwined in the book, as well as in the popular imagination.

The novel’s birth, like Mary’s own tragic arrival in the world, is now the stuff of legend. She writes about it in the revised 1831 version of the book – the 1818 edition had been published anonymously.

Mary began the novel in Geneva, Switzerland, where she had eloped at 16 with Shelley and a group that also included the poet Lord Byron and Mary’s stepsister, Clara Mary Jane Clairmont, known as “Claire”, who was madly in love with Byron and pregnant with his child. The impetuous young Claire, after seeing her stepsister elope with a renowned Romantic poet, decided she wanted one of her own and pursued a largely indifferent Byron relentlessly.

To add to what must have been a charged atmosphere of unrequited love and recriminations, June and July 1816 – dubbed the “year without a summer” – were wet and uncongenial. The assembled party regularly holed up around the fire, telling stories and swapping ideas. On one particular night, Lord Byron threw down the gauntlet, as Mary writes in her introduction: “We will each write a ghost story,” he announced.

Inspired by a vision

In Mary’s version of events, the challenge was a struggle and inspiration finally struck in a waking dream: “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life.”

Attributing her inspiration to a vision could have been modesty on Mary’s part or, as Charlotte Gordon points out in Romantic Outlaws, a tactical move to distance herself from the creation of a novel many believed was too grotesque to be written by a delicate young woman. Whatever the reason, it made for a good story, and Mary knew a good story when she heard one. She describes sitting as a “devout but nearly silent listener” in conversations between Shelley and Byron about galvanism – Galvani’s most famous work involved animating dead animals with electrical currents – and the “experiments of Dr Darwin”.

On an earlier European trip, there had been another source of inspiration. Mary had caught sight of the towers of a castle called Frankenstein, a few miles north of Mannheim, where, legend had it, alchemist Konrad Dippel was so obsessed with finding a cure for death that he attempted to bring stolen corpses back to life.

Death and loss

Which is not to say that Frankenstein came purely from external sources. The novel is full of Mary Shelley – her Swiss surroundings, her passion for the natural world, her loves and losses. The book, which took nine months to write, also corresponds with her own gestation, starting in December 17— and ending in September 17— (Mary famously didn’t specify years in the book). Mary Wollstonecraft conceived in early December 1796, gave birth to Mary on 30 August 1797 and died on 10 September 1797. Charlotte Gordon writes: “By connecting Frankenstein to her own genesis, Mary hints at the many ties she felt to her story… Since the novel is framed by Walton’s letters to Margaret, whose initials were the same as Mary’s now that she had married Shelley (MWS), it is as though she wrote the tale for herself.”

With its deep sense of wildness and loss, dying children and absent mothers – or creators – Frankenstein’s subjects were ones with which Mary was all too familiar. In February 1815, she lost her first child, born prematurely. Not long after her baby died, in a heartbreaking passage in her journal she wrote: “Dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived.” It was a haunting foreshadowing of the creature brought to life in her novel.

Death had accompanied Mary’s entrance to the world. Brought up by her grief-stricken father, she had learned to read tracing the letters on her mother’s gravestone in St Pancras churchyard. It was at Wollstonecraft’s gravestone, too, that, in 1814, she first declared her love for Shelley, a disciple of her father’s who had been captivated by Mary’s flame-haired beauty, fierce intelligence and impeccable revolutionary credentials, as well as “the irresistible wildness and sublimity of her feelings”.

Mary thought her reactionary father would understand – her parents were against marriage and had resisted it initially themselves. Unfortunately, when it came to his daughter, Godwin was more conventional and he disowned Mary when she eloped with Shelley. Nor was he won over by her dedication to him in Frankenstein, which suggested to the world, along with Shelley’s preface, that the poet was the author of the anonymous publication.

Shelley’s influence

As the person closest to Mary, Shelley did, of course, influence Frankenstein, both in terms of his character – he had conducted some pretty macabre scientific experiments himself as a young man – and as an editor, but Mary did the same for him. The pair encouraged and supported each other’s writing throughout their time together. Despite their mutually collaborative efforts, it is rarely suggested that Mary is responsible for Shelley’s work, though the reverse, of course, has been claimed since Frankenstein appeared – and continues to be a matter of debate among some scholars.

The couple married in 1816 following the suicide of Shelley’s wife, Harriet – one of many tragedies that put a strain on their relationship, including the death of their children, Clara and William, which caused Mary to retreat into herself and Shelley to look for attention elsewhere. They lived briefly in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, but preferred to travel in Europe. Sadly, the couple had not recovered from these rifts when Shelley drowned at sea during a storm off the Italian coast in 1822.

Rewriting history

Throughout her life, Mary’s tendency to withdraw into herself during dark times was misinterpreted by those around her, not least her flamboyantly expressive husband. There were depressive tendencies in her family: her mother and half-sister, Fanny Imlay, had both attempted suicide – the latter successfully in October 1816.

Yet Mary believed she had something worth living for: her one surviving child, Percy Shelley, with whom she returned to London, where she pursued her career as a novelist, biographer and travel writer. She also tirelessly edited and promoted her husband’s work, treading a fine line between doing so and keeping peace with her father-in-law, who still blamed her for the scandal of the elopement.

Percy Shelley was devoted to his mother and she to him, but it was with his wife, Jane, that the rewriting of history began. Jane burned the more contentious parts of her mother-in-law’s journals and letters, leaving for posterity Mary Shelley as dutiful wife, mother and daughter rather than the radical talent she truly was. It took the 1970s – and the rise of feminism – to change that.