Regency Britain

Two-hundred years separate us from the start of the Regency era, but the elegant and distinctive buildings created during this period still grace many of Britain’s most beautiful towns and cities

Without the Regency, there would be no Regent’s Park or Regent Street. Brighton would not have its Pavilion. Cheltenham would be devoid of its graceful ironwork balconies and beautiful terraces, and many other British towns and cities would be far less attractive and uplifting than they are.

Of course, the Regency (1811-1820) was a period in British history, but the term has come to describe a style and encapsulate a social era. It all started on 9pm on 19 June 1811, when the Prince of Wales hosted a spectacular party at Carlton House, his splendid London residence, to celebrate the start of his assumption. In January of that year, a bill had been passed in Parliament declaring him Prince Regent, after his father, King George III, who suffered from mental illness, had experienced yet another violent attack and was finally deemed unfit to rule. The Regency lasted until George III’s death in 1820, when the Prince became King George IV.

Flamboyant was the fashion

Flamboyant and fashionable, the fete set the tone for the Prince’s reign. One journalist reported: ‘The state-rooms on the principal floor were thrown open for the reception of the company, wherein the furniture was displayed in all its varied magnificence.’ The poet Tom Moore, one of the 2,000 guests, described the event thus: ‘Nothing was ever half so magnificent… an assemblage of beauty, splendour, and profuse magnificence.’ The main supper table spanned the entire length of the 200ft jewel-like Gothic conservatory. On it, a central basin fed a meandering stream filled with fish. Money and common sense were clearly irrelevant. For three days after the party, the public was invited to view Carlton House. On the last day some 30,000 people stormed the building, leaving a few seriously injured.

The Prince Regent was incapable of restraint. His extravagance involved a love of all things edible, fashionable and beautiful, including a penchant for alluring women. With little interest in politics, he preferred to focus his efforts on – and plough money into – commissioning costly works of art and architecture. His greatest legacy is of course Brighton Pavilion, fanciful, exotic and ever-so-slightly over-the-top. From here, the Prince conducted his liaison with his most famous mistress Mrs Fitzherbert, whose house in Brighton was connected to the Pavilion by an underground passage.

Many of the Prince’s great architectural commissions still remain. Sadly, though, this is not the case of the palatial Carlton House, which the Prince had rebuilt by architects Henry Holland and John Nash to serve as his opulent London residence in the exclusive St James’s district. It was demolished in 1826, just a few decades after its completion. By that date the Prince had become King and had decided that Buckingham Palace was a far more appropriate residence for a monarch. Naturally, he set about enlarging and magnifying this building as well.

Legacy of The Prince Regent

While the Regent was extending his own abodes (and also changing the face of London, see side bar), towns and cities across the country were experiencing a huge population growth, which in turn led to a building boom, particularly in the 1820s and 1830s. At the same time, some towns, particularly those which had mineral springs such as Bath, Brighton, Buxton, Cheltenham and Leamington, became chic resorts where fashionable people flocked to ‘take the waters’. This created the need for places of entertainment, such as ‘pump rooms’, theatres and assembly rooms, as well as elegant terraces and squares built speculatively and often as part of estates (a bit like modern-day housing estates – but much nicer!). And so it was that Regency architecture spread across the country. Before we look at some of its best examples, it’s worth trying to define this elusive style.

Certain elements make it stand out from, say, the more general term of ‘Georgian’, which covers the reigns of all four Georges (1714-1830). While the Regency itself only lasted between 1811 and 1820, art historians believe the Regency style stretched from about the 1790s to 1830. Regency architecture is similar to neo-classical Georgian architecture, but it is more delicate and even more elegant.

Generally (with the exception of Brighton Pavilion which is an architectural ‘one-of-a-kind’), Regency buildings are elegantly restrained, often faced in white stucco, but at the same time adorned with graceful touches such as intricate ironwork balconies, Chinese-inspired pagoda porches, bow windows, classical-style porticos, and classical elements such as columns and pilasters (flat columns). Regency interiors were more sumptuous, characterised by bold, vertically striped wallpaper, lots of gilding and elegant furniture, vases and ornaments inspired by the antiquities of ancient Greece and Rome. The most famous Regency designer was Thomas Hope, whose work can be seen at the Victorian & Albert Museum in London. Perhaps it is this mix of restraint and luxury, of purity and adornment that makes the Regency style so appealing.

Best places to see Regency architecture

So, where to go to see the best Regency architecture? Aside London (see Regency Master), the seaside city of Brighton and Hove has perhaps the biggest and most excellent concentration of Regency buildings. Elegant crescents and terraces aren’t hard to find, but arguably the most stunning Regency jewel here is Brunswick Town in Hove’s conservation area. The scheme was designed by local architect Charles Augustin Busby and includes the superb Brunswick Square and Brunswick Terrace, which remain two of the most desirable addresses in town. The Brunswick Square buildings ripple with voluminous bow windows, almost echoing the movement of the waves just a few yards away.

It is shocking to think that in the 1940s this area, along with other terraces and squares of the Brighton and Hove seafront, was threatened with demolition. The Regency Society was formed in 1945 to fight this impending threat and still campaigns for the preservation of Brighton and Hove’s architectural heritage. The Grade-I listed Regency Town House at no. 13 Brunswick Square is now a centre dedicated to the architecture and social history of the Regency period. It holds exhibitions, as well as guided tours of the house. Other grand Regency schemes to look out for in the city include Adelaide Crescent, Bedford Square, Powis Square, the Royal Crescent, Lewes Crescent, Montpelier Crescent and Regency Square.

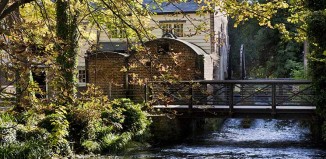

Cheltenham’s heyday as a spa town (c. 1790-1840) exactly corresponded with the Regency style’s lifespan, so it’s perhaps not surprising that it has been described as England’s most complete Regency town. Its aura of refinement is in no small part due to its gleaming town houses, terraces and squares, often embellished with delicate ironwork balconies. The town’s impressive Promenade, laid out from 1817-8, recently won the title of ‘Britain’s Favourite High Street’ and is perhaps its most obvious highlight. But walk beyond Cheltenham’s shopping heart and you will come across the fashionable Montpellier area, with its delightful Montpellier Walk, where large caryatid figures grace a semi-circular building, almost inviting you to explore the charming rows of shops and cafés. Further afield you will find the Pittville area, with its imposing Italianate villas, picturesque garden and glorious Pump Room.

As you walk around the town, you might want to try spotting the delicate black or white ironwork balconies: the more you look, the more you’ll find.

Many of the finest buildings in Bath were actually built in the decades before the start of the Regency era, but a visit here will give you an enticing glimpse into what Regency society life was like. In the Assembly Rooms, you will discover where the fashionable set went to dance (as described in the novels of Jane Austen), drink tea, play cards and attend other important social functions. The powder-blue 100ft-long Ballroom, with its five original crystal chandeliers, could hold up to 1,200 people. The other public rooms – the Octagon, Card Room and Tea Room – are equally enchanting and can be booked for weddings and grand receptions. Here you will also find the Fashion Museum, which features, among other displays, items of Regency dress. Meanwhile, in Bath’s Pump Room you can enjoy a taste of the city’s hot spa water, if you are that way inclined!

Other British towns and cities, including Harrogate, Bristol, Leamington Spa, Tunbridge Wells and Newcastle, are home to many other Regency buildings, each as pleasing and delightful as the other.