Plymouth – City by the sea

In a city that sustained decimating aerial bombardment during the Second World War, it is perhaps remarkable that any of Plymouth’s historic buildings are still standing. However, it’s cheering to discover that a number of the city’s most prominent landmarks weathered the storm, emerging from the dust and rubble of the Blitz of March 1941 to continue sharing their story today.

Situated between the rivers Plym and Tamar in a beautiful natural harbour on the south Devonshire coast, the city first started life as a small Saxon fishing village named Sudtone (or Sutton). Outshining neighbouring communities such as Plympton, thanks to its advantageous position, the village thrived, trading in wool and Dartmoor tin. By the 14th century, the hugely expanded Sudtone had assumed its new moniker of Plymouth.

For a port city, Plymouth is prettier, cleaner and more culturally diverse than most, offering a desirable place for its residents to live. Over the centuries it has grown to take advantage of the coastline’s curves, with a dockyard here, a marina there and even an Art Deco lido thrown in for good measure. The city’s manmade harbour, known as the Barbican, is now an exclusive area, with a colourful array of fishing boats and yachts that bob gently while the Continental-style cafés buzz with the daily gossip. It’s a very different scene from a mile further along the coast, where ferries and naval vessels are loaded, unloaded and serviced at the city’s bustling port.

Visitors have arrived here in droves for centuries – many too preoccupied to notice their surroundings. From the 1600s Plymouth was many people’s last taste of native soil as they stepped off the quayside to board emigration or convict vessels bound for America, Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

“Various plaques and tablets commemorate Plymouth’s part in forming the New World,” explains Blue Badge Guide Jane Dymock as we examine the walls of the Barbican’s West Pier. “The majority of visitors are interested in seeing the monument to the Pilgrim Fathers who departed on the Mayflower on 16 September 1620. There were around 100 of them on the voyage. Persecuted for their Puritanical beliefs, they had petitioned King James I to allow them to start a colony in America.”

In previous years, Holland had been the destination of choice for fleeing Puritans, but many were worried that their children would lose their English identity. They risked everything to start anew, joining the Mayflower passengers. After 66 cramped and sickly days at sea, stormy weather finally forced the ship to land, by coincidence, in Plymouth, Massachusetts, which has been named years before their arrival. After settling into their new surroundings, the Puritans went on to establish one of the first successful permanent English colonies in North America, following in the footsteps of the English colonists in Jamestown, Virginia. Although many of the Plymouth colonists perished from disease and malnutrition, the colony survived and it is thought that there are around 20 million descendants of the Mayflower Pilgrims in the USA today.

An arch monument on the Barbican commemorates the voyage, and a flight of steps known as the Mayflower Steps descend to the water, though Jane explains that these were, in fact, created a century later: “The likely point where the Pilgrims left English soil is thought to be below one of the cellars in the Admiral MacBride pub opposite, where the waterfront would once have fallen.

Another plaque in the pavement states that the Tory was the first colonisation ship to New Zealand from Plymouth in 1839. “Voluntary migration began in the 1800s; prior to that it was for convicts or separatists only. Unlike other ports we treated our emigrants very well before their departure, making sure they were fit and ready to undertake the journey ahead.” The last few nights that the Pilgrim Fathers spent in England would have been at Island House, just a stone’s throw from the water’s edge, which bears their names today.

Plymouth played its part in the slave trade along with many other port cities; it was in fact the first place to profit due to a Plymothian opportunist named Admiral Sir John Hawkins, who is widely acknowledged to have pioneered the country’s slave trade. “This is not something the city is proud of, but many people don’t realise that the abolition of slavery was heralded by the passionate Quaker community here in Plymouth. They brought to light the trade’s inhumanity by producing the Brookes slave ship diagram – a cross section of the deck showing horrific conditions of carriage.”

Plymouth was also the stomping ground of seafarer and privateer Sir Francis Drake. Feted for his defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, Drake was also responsible for much of the city’s wealth in Elizabethan times, and was quietly favoured by Queen Elizabeth who is said to have enjoyed the sparkling bounty he plundered.

“For me, the most fascinating period of Plymouth’s history is the 18th century, with the development of the navy,” Jane reveals. “The port became such a hub – it was the prize capital of the British naval world. The city prospered under privateering. At one time in the late 1700s there was so much claret, stolen from enemy ships, that it couldn’t be contained or sold and barrels of it were taken out to sea and used by the navy as target practice.”

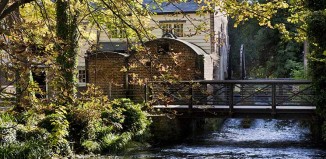

The city’s oldest road, New Street, winds away from the harbour, part of a network of narrow routes and alleyways on the Barbican. In Drake’s days, it housed vaults for the storage of goods taken from foreign ships, ranging from gold bullion to wine. Just a couple of buildings from the era survive and the Elizabethan House Museum is a fine example.

Sadly, many of the fine Tudor and Jacobean properties were destroyed, long before the Blitz, but all was not lost. The first female member of Parliament, Nancy Astor became an honorary Plymothian when she represented the Plymouth Sutton district in 1910. The American moved to England in 1904, married the wealthy Waldorf Astor two years later and was instrumental in saving many of the city’s historic buildings, donating generously to ensure their survival. The couple lived at the prestigious Elliot Terrace, which can still be visited on the Hoe.

Given the extent of the bombing during the Blitz, it is remarkable that a clutch of historic buildings survived; the Prysten House in Finewell Street is one of them. This 15th-century merchant’s house situated just behind St Andrew’s church is thought to be the oldest dwelling house in the city centre (since transformed into a fashionable restaurant), but has been kept in pristine condition, constructed of local limestone brickwork. “Look closely at the buildings you pass,” says Jane. “You’ll be able to see Jurassic fossils in the stones of many.”

The Plymouth Gin building on the Barbican is another ancient treasure. Dating back to 1430 when it was known as the Black Friars Distillery, it is thought to have been home to an order of Dominican friars. It is the city’s oldest building and has been producing gin, using the integral ingredient of Dartmoor water, since 1793. Miraculously it escaped the 1941 raids and when local sailors – huge fans of the tipple – heard news of the Blitz they rejoiced that the gin building had, at least, been spared.

Turning left at 34-40 New Street will take you into a neatly kept Elizabethan Garden – a quiet space filled with summer roses and period planting, with beautiful medieval carvings set in the stonework. It was formed in the 1970s within the shells of fallen housing and is one of the area’s best kept secrets. Just behind it is the infamous Castle Street. “In Drake’s time every other house was an inn and every inn a brothel!” says Jane.

In medieval times the Barbican contained a castle – hence its name – designed to defend the waterways from attack. As a wealthy port, the city was vulnerable and had to protect its resources of tin as well as its foreign treasures. Little or nothing is left of the castle as the Royal Citadel replaced the Barbican in 1670, merging it with a neighbouring garrison called Drake’s Fort. “The story goes that there were more guns pointed over the city than at the sea,” says Jane. “Plymouth was against Charles I throughout the Civil War, and even when the city was besieged by Royalists, it stood firm.” Today, the Citadel is home to 29 Commando Regiment Royal Artillery who work closely with the Royal Marines.

Plymouth Hoe (Hoe is a Saxon word meaning high ridge) offers panoramic southerly views from its limestone cliffs. The harbour itself was formed by a now extinct volcano at least 280 million years ago. Formerly under the military ownership of the Citadel, the Hoe became a public park in the late 1800s, offering views out Drake’s Island, where the seaman once hid his ship before sending a scout to check he was still welcome in England.

Unmissable on the Hoe is the red and white lighthouse, Smeaton’s Tower, open year round for people to admire the views 72ft up. For decades it stood on the Eddystone Rocks, 14 miles out to sea, and its replacement now just visible with the naked eye. It was removed from service in the early 1880s after it was discovered that the rocks underneath were unstable. Its design is still used as the benchmark for all lighthouses worldwide.

Separated from Cornwall by the River Tamar, over which Brunel completed his Royal Albert Bridge in 1859, Plymouth is a major centre for travel links and commerce for the south west, and is a place of constant change. It has inspired artists, architects and politicians, as well as the naming of 43 Plymouth ports worldwide. As we all know, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

The Plymouth Tourist Information Centre at 3-5 The Barbican can organise area tours and accommodation. For more information go to www.visitplymouth.co.uk; or www.blue-badge-guides.com