Cardiff

David Atkinson

The city of Cardiff is a master of reinvention. The heartland of Wales’ industrial heritage has been reborn through urban regeneration as a hub for the Welsh cultural scene and a living, modern city that remains in touch with its past. But this winter two new projects will highlight the attractions of exploring Cardiff’s heritage through fresh eyes.

The first of these is The Cardiff Story, a new museum tracing the story of daily life in the city over the centuries, which is settling into its new home above the Tourist Information Centre in the city’s Old Library building. Aside from array of the exhibits themselves, the Victorian tile-lined corridors, built in the Staffordshire Potteries and moved en-masse to Cardiff around 1880, positively resonate with local history.

At the same time, the Castle Quarter, a £4 million pedestrianised shopping area at the heart of the historic city centre, has connected the top end of High St with Cardiff Castle. The Quarter, designed with a nod to London’s Covent Garden or Brighton’s Lanes, is hosting a Christmas market in December, followed with a series of public-art events. Beyond the familiar high street stores, it is also home one of Cardiff’s hidden gems: a rabbit warren of Victorian shopping arcades packed with quirky local traders.

“The historic Castle Quarter is what makes Cardiff different to other UK cities,” says long-term Cardiff resident, Harriet Davies, an American ex-pat who runs the New York Deli in the High Street Arcade. In recent times Harriet has been busy mobilising the 55 independent shopkeepers from the High St, Duke St and Castle Arcades to produce a new awareness-raising map of the Castle Quarter, highlighting interesting places to eat and shop, and unusual things to see. “The streets between the market and the castle are the old heart of the city, dating from the 1860s,” she adds.

For a more complete historical perspective on the city, you can head to the new visitor centre at Cardiff Castle, where its is possible to watch a short film tracing the story of the city, from its early beginnings as a Roman settlement through its boom at the forefront of the coal trade, to its more recent reinvention as Wales’ vibrant cultural capital.

The story starts with a Roman fort founded on the site of the current-day castle between 55 and 260AD, which was named Caerdydd, meaning the fort (caer) on the River Taff (dydd). When the Normans arrived between 1066 and 1135, the erstwhile Roman settlement was selected as the site for a motte and bailey castle and Robert Fitzhamon, the conqueror of Glamorgan, was charged with its construction. But it was the Bute family, the aristocratic Scottish landed gentry, who really shaped modern Cardiff. They inherited Cardiff Castle in the 18th century and, when the northern Welsh valleys kick-started the iron-making and coal-mining boom in the 19th century, the wealthy Butes set about turning Cardiff into the energy-exporting capital of the world.

The Second Marquess, in particular, bankrolled Cardiff’s rapid development and, by way of celebration, commissioned the architect William Burgess in 1869 to transform the castle into a Victorian fantasy of neo-Gothic proportions, adding a clock tower and redecorating extensively with flight-of-fancy follies. The Banqueting Hall, with its elaborate winged cherubs and minstrels’ gallery, survives today as testament to the Marquess’s elaborate vision. Under the governance of the Butes Cardiff grew and prospered, with the population growing from around 2,000 in 1800 to 200,000 in 1900. At the same time Cardiff docks flourished from 1830 through to 1960, handling 13 million tones of coal per year at their peak.

“It was like the Klondike,” explains Blue Badge Guide, David Thompson. “Cardiff went from a backwater to a thriving urban metropolis with the surge of people moving to work in the growing industry at the docks,”

The boom years were short lived, however. The Butes sold the castle back to the city of Cardiff for £1 in 1947 and industrial decline took hold soon after the Second World War. Cardiff was proclaimed the first ever capital of Wales in 1955 (previously Wales had no official capital), selected because Cardiff had been a major international port during the industrial revolution and boasted the most impressive architectural riches thanks to the Butes. But even elevation to capital-city status could not halt the economic stagnation throughout the late 20th century. Only when the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation was founded in 1988 to bring major urban regeneration to the city and, especially, it’s run-down, pride-shattered docklands, did Cardiff’s fortunes really start to change. The subsequent transformation of the city centre and the bay was nothing short of miraculous.

“Today Cardiff has a real capital-city feel,” says David Thompson. “From gnarled old residents to teenagers, everyone shares the sense of civic pride in the way Cardiff has been reborn.

“These days Cardiff feels much more Welsh with the rise of the Welsh language in the 1960s and the devolution of the Welsh Parliament in 1999,” he adds. “It has become a cultural hotbed with its live music scene, theatres and major sporting events at the Millennium Stadium.”

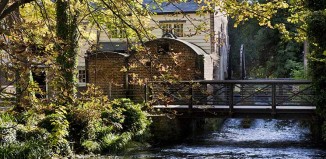

Wandering through Bute Park, with views across to the Castle through the trees, leads to Cardiff’s grandiose Civic Centre. The European-style plaza, fringed by architecturally ornate buildings constructed from white, Portland stone (the same as the White House), again have the Bute family to thank for their aesthetic charm. Built at the turn of the 20th century, the grouping of the National Museum, Law Courts, City Hall and university buildings were commissioned by the Third Marquess as a statement of intent to project Cardiff onto the world stage.

A major attraction these days, apart from the outdoors winter-wonderland park, with its big wheel and ice-skating rink on the plaza each December, is the National Museum, where the Origins Gallery traces the development of life in Wales from the Red Lady of Paviland Cave, the earliest known, formal human burial in Britain, onwards. The upper-level Impressionist Gallery features works by Monet, Van Gough and Renoir that were recently returned to the museum after a period on loan in Washington DC. Heading southeast to Cardiff Bay, the transition from historic centre to striking modern architecture couldn’t be more marked. The Wales Millennium Centre, with its distinctive golden roof and mauve slate-paneling facade, has become the icon of contemporary Cardiff. It opened (somewhat belatedly given its name) in 2004 and is the capital’s major arts hub today, providing a home to the Welsh National Opera. Alongside is The Senedd, the National Assembly for Wales building, which followed two years later. These two iconic buildings, both of which offer guided tours and stunning views of the bay through their glass façades, have put Cardiff Bay back on the map, with the adjoining Mermaid Quay, a haven of café culture, making it a lively spot for families and culture vultures alike.

Another, more low-key building in the bay is notable for revealing the story of one of Cardiff’s best-known sons. The Norwegian Church Arts Centre was founded in 1868 and extended into its present form in 1889. The children’s’ author Roald Dahl, born to Norwegian timber-trading parents in Cardiff in 1916, was baptised in the chapel and lived in the city until the age of 12. Today it stands at the entrance to Bute West Dock and acts as a cosy café and a contemporary arts centre, hosting atmospheric carol services in its tiny chapel each December, although this year it will be closed over winter for refurbishment. A small exhibition in the chapel traces the story of the young Roald.

Outside the church, a stoic, white-marble statue of Scott of the Antarctic, who set sail from Cardiff for Antarctica in 1910, stands guard over the seawall. The fact he was beaten into seconds place in his task by the Norwegian seaman Roald Amundsen is not lost on the current-day owners of the church.

Back at the New York Deli, Harriet Davies is busily preparing the house specialty sandwich, a White House Special – that’s ham, salami, pastrami, turkey, coleslaw and sauce, and the mood is upbeat. Although Cardiff’s fortunes have known many highs and lows over the years, there’s a palpable sense that things are on the up once again and that the Castle Quarter will encourage people to eschew the chain stores in favour of Cardiff’s historic arcades. “This Quarter was the heart and soul of Cardiff from the 1860s onwards,” says Harriet proudly. “And finally, it’s alive again.”

For more information about visiting Cardiff call: 029 2087 3573 ; www.visitcardiff.com