Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee: A United Front

Seemingly opposed in class, politics and personality, Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee forged an unlikely friendship during wartime as David Cohen reveals.

If Winston Churchill had not been born at Blenheim Palace, as he was in 1874, would he have been a different person? David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister who steered Britain to victory in the First World War, once suggested that Churchill hated communism not just because of its ideology, but because Churchill’s ‘ducal blood’ was revolted by the way the Bolsheviks slaughtered the Tsar and his family after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

During the Second World War, Churchill entered into a wartime coalition government with his Labour Party counterpart Clement Attlee and the pair were united by their opposition to communism; Churchill likened the comrades to “baboons”, while Attlee labelled them “gratuitous asses”.

Attlee was born in far more modest circumstances than Churchill. His father was a solicitor. As a boy, Attlee lived in a comfortable house on Portinscale Road in the London suburb of Putney. Attlee’s ancestry was not a distinguished one, while Churchill could trace his lineage back to the Duke of Marlborough, who won the Battle of Blenheim in 1704 and then became Queen Anne’s chief minister. Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph Churchill, had also enjoyed a successful political career, until he sabotaged it when he resigned as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1886.

Given their social differences, it seems amazing that Attlee and Churchill shared a governess, Miss Hutchinson, a woman Churchill never liked. She left the Churchills when the future Prime Minister was six years old, and later went to work for the Attlee family. She taught Attlee until he started school, aged nine. “She could never have thought that the two little boys were destined in turn to be Prime Minister,” Attlee marvelled in his autobiography, As it Happened.

Miss Hutchinson was not the only person who looked after both men. After Churchill lost the 1945 election to Attlee’s Labour Party, he told his former deputy that a British Prime Minister could hardly meet Harry Truman, the new President of the United States, and Comrade Stalin without a valet. He insisted on lending Attlee his own man. The Russians were amazed.

Curiously, no book has focused on examining the relationship between Attlee and Churchill, or tried to discover how they managed to achieve that rarest of political feats: a successful collaboration. Most historians seem to have taken this almost for granted. My latest book, Churchill & Attlee – The Unlikely Allies Who Won the War, was an attempt to examine what made that coalition possible and identify what divided and united the two men in terms of policy, personality and principles.

With his famous ducal heritage, it is perhaps not strange that Churchill proved extremely ambitious from his youth. Attlee was different. He could compose witty verse and, in later life, he wrote a private poem that reflected on his election as Prime Minister in the surprise Labour landslide of 1945: “Few thought he was even a starter/ There were many who thought themselves smarter/ But he finished PM/ CH and OM/ An Earl and a Knight of the Garter.”

The First World War had a profound effect on both men. Churchill was forced to resign as First Lord of the Admiralty after the disaster at Gallipoli, where Turkish troops defeated a combined British, Australian and New Zealand force. Attlee fought at Gallipoli and was the second last man to be evacuated from Suvla Bay. Having witnessed the catastrophic effects of military muddle and delay, Churchill and Attlee were determined the same mistakes would not be repeated in the war against Hitler.

Although Churchill was a Conservative (or ‘Tory’) for most of his parliamentary career, while Attlee was a socialist, they shared more political similarities than one might expect. Both were reformers who proposed the abolition of the House of Lords. Attlee noted in As it Happened

that a Colonel Vigne, with whom he played bridge as he sailed to Gallipoli, branded him a “damned democratic, socialist, tub-thumping rascal”. Nevertheless Attlee, like Churchill, was a staunch monarchist.

As a trained psychologist, I was keen to mine the archives for psychological material. Two things, I believe, helped Attlee cope with Churchill, who was prone to mood swings and sometimes cried in public. It has been claimed that Churchill suffered from depression, but I would argue that his personality contained elements of manic-depressive disorder. Attlee was well versed in the psychological theories of his time. This, and the fact that Attlee’s wife Violet was prone to depression, enabled Attlee to cope with Churchill after he became Churchill’s deputy in 1940.

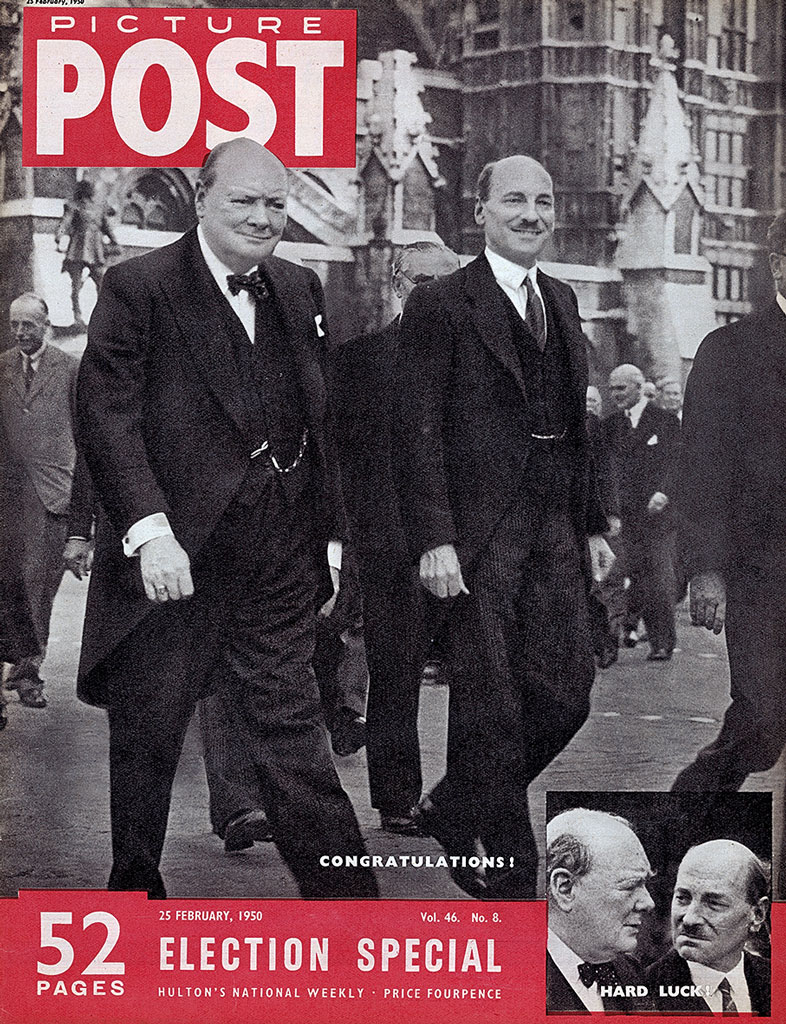

In the 1920s, and for most of the 1930s, Churchill and Attlee opposed each other on many major issues, including the future of India and the value of socialism. But in May 1940, when Attlee brought the Labour Party into coalition with Churchill’s Tories, the two men forgot their differences and focused on defeating the Nazis.

After the war was won in 1945, Churchill was unstinting in his praise of the Labour leader. “Our only differences in outlook were about socialism, but these were swamped by a war soon to involve the almost complete subordination of the state. We worked together with perfect ease and confidence.” Attlee’s efficiency meant Churchill only needed to attend the House of Commons “on the most serious occasions”.

According to Attlee’s daughter-in-law, Attlee was loyal to Churchill for another reason. In a 1997 interview in The Independent, Margaret, Countess Attlee, said her husband, the second Earl Attlee, never took the Labour whip in the House of Lords after succeeding his father. She added: “I have always believed that Clement was a Conservative with a conscience. He was not a tremendous left-winger and that was the family tradition.”

Churchill and Attlee were not far apart on many social issues. One of the great achievements of the wartime coalition was the Beveridge Report of 1942, which remodelled social benefits and paved the way for the National Health Service. Some contemporaries claimed that Churchill bullied Attlee, but Attlee, who had been shy as a young man, stood up to Churchill often.

Following his Labour Party’s landslide victory in 1945, Attlee worried about the effect the defeat would have on Churchill. When Labour was returned in 1950, but this time with a tiny parliamentary majority, Attlee was for the only time in their relationship less than courteous to Churchill. He accused Churchill of misleading Parliament on the issue of Britain’s nuclear research, and of being too deaf to hear what he did notwant to hear.

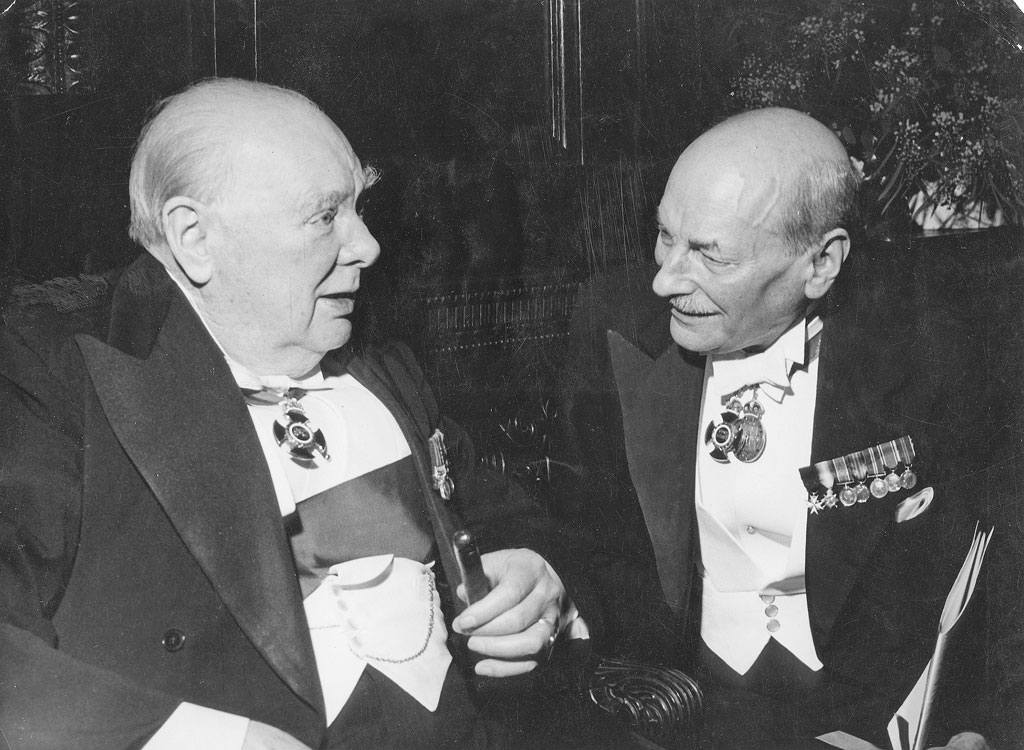

The following year saw Churchill regain the leadership, yet he retired ahead of the 1955 General Election, which the Conservatives also won. Taking their seats in the new parliament, Attlee and Churchill displayed their obvious mutual respect and affection for each other. “Attlee was very kind to me when I took my seat,” Churchill said.

An MP spied Churchill, who was not so steady on his feet, advancing up the floor, and shouted: “Churchill!” People in the public gallery clapped, and MPs crowding the benches waved their order papers, cheering madly. Attlee rose from his seat, took Churchill by the arm and led him forward. They shook hands. Attlee insisted Churchill take the oath before he did; the whole House rose and applauded.

Labour’s Herbert Morrison patted Churchill affectionately on the back. Churchill shook Morrison’s hand warmly. Then Churchill signed the roll of members and waited for Attlee to do the same. The two men walked in unison from the Chamber. They were comrades-in-arms nearly to the end.