St Thomas Becket: A turbulent priest

On the 850th anniversary of his canonisation, Diana Wright assesses where it all went wrong for St Thomas Becket

As monks were singing vespers amid the twilight glow of candles in Canterbury Cathedral one winter afternoon, the peace was violently shattered by a shout for “Thomas Becket, traitor to the king and the kingdom.”

Four armed knights fortified by liquor burst through the cloister door. Having already faced down his assailants in a fiery altercation in the adjacent archbishop’s palace, Becket defiantly replied: “Here I am, not a traitor to the king, but a priest of God.”

Horrified clergy urged the archbishop to flee but he stood his ground as the sword-wielding thugs rushed at him and tried to manhandle him outside. Becket resisted by clinging to a pillar; his fur cap was dislodged from his head, there was pushing and shoving, and he was struck to the ground. Lying bloodied on the floor, he murmured: “For the name of Jesus and the defence of the Church I am willing to die.” The assassins finished off their sickening deed and escaped.

News of Becket’s murder within the sanctity of a cathedral on 29 December 1170 stunned God-fearing folk across Europe. Reports also circulated of miracle healings of people who daubed themselves with droplets of his blood collected from the scene by ghoulish souvenir hunters.

In 1173 – this year is the 850th anniversary – Thomas Becket was declared a saint and his shrine at Canterbury Cathedral would become one of the top four sites in Christendom for medieval pilgrimage.

But what do we really know of St Thomas Becket and why had his friendship with King Henry II turned to such bitter hatred?

Who was St Thomas Becket?

Born in London circa 1118, Thomas was the only surviving son of an immigrant Norman merchant, Gilbert. He had three sisters and was reportedly deeply attached to his devoutly religious mother, Matilda (who died when he was 21). The family was comfortably well off, but when he later mixed in elevated courtly circles Thomas would be sensitive about his modest roots, fending off social slights with the retort: “I prefer to be a man in whom nobility of mind creates nobility, rather than one in whom nobility of birth degenerates.”

Educated in Surrey, London, and Paris, he was an unexceptional scholar and, according to one friend, “indulged in the rakish pursuits of youth… was proud and vain”. But he soon focused his energies and talents when – thanks to his father – he entered the household of Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury, who sent him to study civil and canon law in Bologna and Auxerre. Grown into a tall, dark-haired, slender man, and now proving himself “quick of learning” with a tenacious memory, Thomas became the archbishop’s trusted agent and was made Archdeacon of Canterbury.

St Thomas Becket and Henry II

Change was afoot in the wider world as well as for Becket. In 1154, after some eight years of civil war across England, King Stephen died and was succeeded by Henry II. Theobald promptly recommended his protégé as the new king’s chancellor, a post that Thomas embraced with alacrity. He was 15 years older than Henry, but the pair became such friends that it was said they had “but one heart and one mind”.

Thomas relished the courtly lifestyle, hunting with Henry, lavishly entertaining guests, conducting embassies and even soldiering with the king. Meanwhile, if Theobald had hoped his placement of Becket would help to champion Church matters in its perennial struggles with the Crown, he was sorely disappointed; the chancellor “put the king before God” in his administrative duties: enforcing the collection of royal dues from landowners, churches and bishoprics that included taxes to the detriment of the clergy. Rather shamefully, Thomas even failed to visit his old mentor as he lay dying.

Yet aside from public appearances, Becket was sufficiently perceptive to realise that cunning, quick-tempered Henry was “a tester of character”: seeking out a person’s weaknesses to exploit unless they stood up to him. Their friendship was about to be tried.

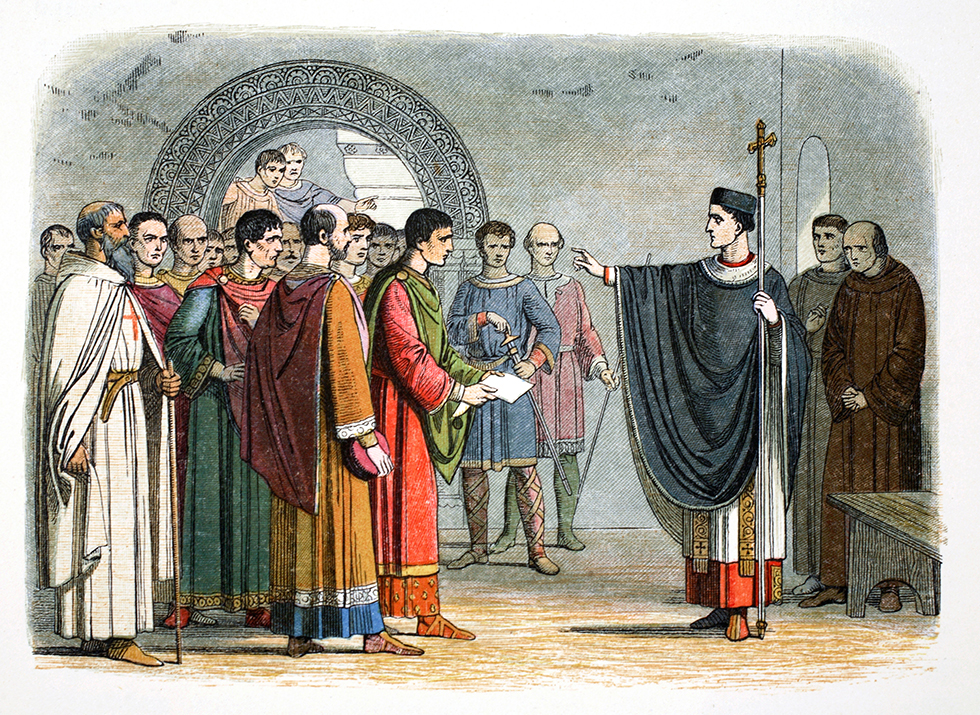

Thomas was relatively low in the clerical pecking order, but Henry wanted him to succeed Theobald as Archbishop of Canterbury. Becket declined but then was persuaded “more for love [of Henry] than for the love of God”, as he later admitted. Intent on reforming the Church and drawing as much power as he could into royal hands, the king thought he had pulled off a masterstroke in getting his friend into such a pivotal position.

What happened next has always puzzled historians, for “on a sudden”, it was said, Becket metamorphosed from a pleasure-loving courtier into a devout ascetic, as determined to uphold the rights and privileges of the Church as Henry was to assail them. Had he undergone some sort of spiritual conversion of character and conscience? Or was he simply as ambitious for power as the king?

Whatever now motivated Becket, he was not going to roll over and do Henry’s bidding, and so the bickering began. Among other things, the king wanted “criminous clerks” to be tried by lay courts rather than by bishops who meted out milder punishments; and he wanted greater royal control over Church revenues and elections. Becket stubbornly objected, defending the independence of the Church.

The murder of St Thomas Becket

In 1164 matters came to a head when Henry tricked Becket into verbally agreeing to give ground in the Constitutions of Clarendon (16 legislative articles issued by Henry relating to Church/state relations which ultimately tried to curb the power of the Church). However, Becket revoked his agreement as soon as he saw the full extent of the demands written down. The furious king summoned Becket to a trial, accusing him of embezzlement and other infringements when chancellor. Under no illusions that Henry was out to ruin him, Thomas fled to France.

Over the next six years of Becket’s exile, arguments with Henry continued. Becket excommunicated various royal allies, and there were appeals from both sides to the Pope – Louis VII of France and papal legates even tried to broker reconciliations.

Eventually a brittle truce was engineered, and Becket returned to England in December 1170 amid popular public rejoicing. Before the month was out, he would be dead. The flashpoint came when Henry heard that Becket was continuing to excommunicate ‘hostile’ royal servants and refusing to lift his earlier excommunication of ‘delinquent’ bishops sympathetic to the king.

Henry’s angry “Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?” is apocryphal but accounts of his outburst all point to him railing that no one ever avenged him of the wrongs he had suffered “by a low-born clerk”. Four knights heeded the words literally, with fatal consequences for Becket.

Henry, apparently, was shell-shocked at the deed, but was absolved after doing public penance at Canterbury in 1174, and the Pope ordered the four assailants to serve as knights in the Holy Land.

The legacy of St Thomas Becket

Meanwhile a major pilgrim industry blossomed around St Thomas Becket’s (since vanished) shrine.

Life for St Thomas Becket life had been colourful, his rise meteoric, and his mark on history was written in the indelible blood of his martyrdom. It is said that he could be too impetuous and was too intransigent towards Henry when greater diplomacy might have served him better, but he knew the “tester of character” he was dealing with. In the final analysis he defied a royal tyrant, and he gave his life for principles he believed in. Battles between Church and Crown would continue for generations to come.

This extract is from our April/May 2023 issue of Discover Britain, which will be on sale from 3 March. Get your copy here.

Read more:

South West 660: The new coastal route for South West England