Explore Ruskin’s Cumbria

Celebrate the legacy of one of Victorian Britain’s most forward-thinking talents. David Atkinson visits the Lake District where Ruskin’s Romantic vision took flight

John Ruskin was the original polymath. A leading light in the Romantic movement and an intellectual voice of Victorian Britain, his writing informed the work of authors, thinkers and activists as diverse as Leo Tolstoy, Marcel Proust and Mahatma Gandhi. He championed the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and tackled many key issues of the Industrial Age, his big-picture clarity helping warn of environmental impact. Yet the scholarly gentleman who made his home on the banks of Coniston Water has fallen from fashion in comparison to his fellow Lake District writers such as William Wordsworth and Beatrix Potter.

Yet a series of exhibitions and events, centring upon his Cumbrian home, marking the bicentenary of his birth in 2019 changed that. His legacy, not only on William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement in Britain but also on the international stage, is huge. After all, his eye for aesthetics and championing of artisan crafts inspired the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright and Yanagi Soetsu’s Mingei folk art movement in Japan among others.

“Ruskin is part of Cumbria’s DNA,” says Howard Hull, the director of Brantwood, Ruskin’s former home, which is now a museum dedicated to his life and work. “His message is very profound, yet also simple: the importance of collaboration, not competition. As societies, and individuals, we need to collaborate with each other and with the world around us.”

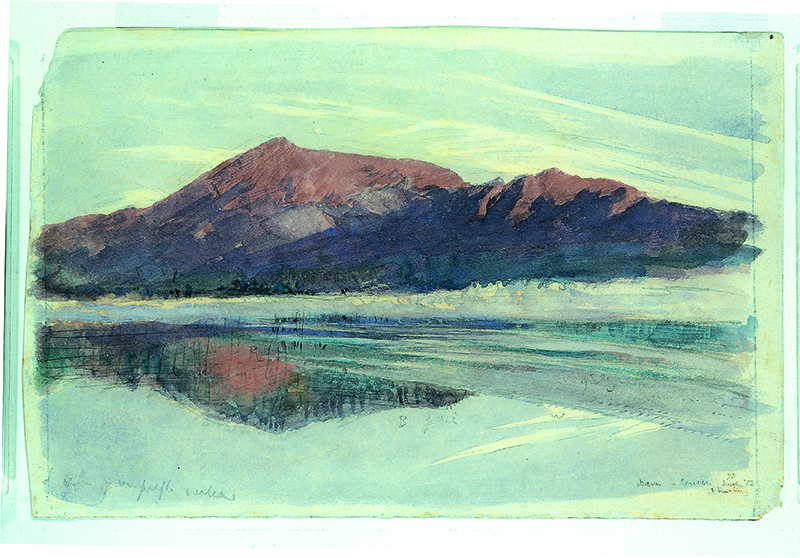

While the Romantics poets such as Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge were the first to craft purple prose about the beauty of the Lake District, a new movement of artists was also discovering Cumbria in the early 19th century. Inspired by Gainsborough before them, Britain’s finest artists of the era, JMW Turner and John Constable, both journeyed north in search of those quintessentially brooding Lakeland vistas. Ruskin picked up their Romantic mantle and evolved it. “He combined Romanticism with a harder look at the social and environmental questions of the day. He understood the connectedness of things — a message still relevant today,” adds Hull.

“The clarity and power of his writing, mixed with his sense of humanity, made him the pre-eminent thinker of the Victorian era, but also one of the most vilified,” adds Vicky Slowe, the director of the Ruskin Museum in the village of Coniston, which is situated across the lake from Brantwood. “Ruskin talked about the welfare state, minimum wage and environmental warming. He was effectively speaking out against the Industrial Revolution.”

John Ruskin was born in London on 8 February 1819 to a devoted, wine-merchant family, who pushed him academically and countered his poor health with Grand Tour-style trips to take the air in the Swiss Alps. After graduating from the University of Oxford, Ruskin started to build a reputation as a writer and lecturer. His 1843 work, Modern Painters, written at the age of just 24, made his name. It started as a defence of Turner but, extending over five volumes, went on to discuss landscape, religion and art. He would go on to become the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford, where Oscar Wilde and Canon Rawsley (the latter one of the founders of the National Trust) were amongst the undergraduates.

Ruskin’s personal life was more troubled, however. He had married Euphemia Gray, the beautiful 19-year-old daughter of family friends, in 1848. But the marriage was an unhappy one and, at a time when polite society couldn’t countenance divorce, the marriage was annulled some six years later. She was then free to marry Ruskin’s protégé, the Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais, who had joined them on a holiday to Scotland. It’s a story retold in the 2014 film Effie Gray, scripted by the British actress Emma Thompson.

“Hampered by his ill health and overprotective parents, I fear Ruskin cut a bit of a lonely figure,” explains Slowe, as she introduces the museum’s collection, which includes a letter, written by a nine-year-old Ruskin to his father in perfect, copperplate handwriting.

“I think it’s unfair to say he didn’t like women,” she adds. “The marriage was rather forced upon the couple and, in the end, I believe he was trying to act chivalrously, protecting Effie from being [seen as] the scarlet woman.”

Ruskin’s move to the Lake District, following his mother’s death in 1871, marked the beginning of a golden period in his professional life. It remained his main home until his death in 1900.

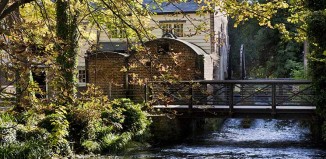

Today Brantwood, set in a 250-acre woodland estate on the eastern side of Coniston Water, is a testament to his aesthetic tastes in architecture, gardening and design. Badger’s Cottage, a converted staff cottage within the grounds, can be rented through The Coppermines and makes the perfect base for exploring the location that inspired Ruskin to write some of his most profound work.

“Brantwood was a place of healing for him, escaping the pressures of London,” says Hull. “Here Ruskin perfected his eye, his openness to see beyond the superficial. He shows us how, by seeing clearly, we deepen our relationship with the world.”

With its stately desk and an armillary sphere, Ruskin’s study at Brantwood was used to observe the movements of the stars. He worked each day in the early morning before tending to his estate in the afternoon. A picture on the wall shows the author sat in his favourite armchair, overlooking the lake. The dining room, meanwhile, commands a superb view across the lake to the Old Man of Coniston, a 2,600-foot peak that dominates the landscape.

After several years, Ruskin suffered a series of mental breakdowns and increasingly retreated from public life to lead a more reclusive existence at Brantwood. In the bedroom, he experienced a series of harrowing hallucinations that culminated in a psychotic episode on Good Friday 1878. “He describes in his letters how the sheer volume of thoughts in his head would spiral out of control,” says Hull. “He would weave beautiful tapestries of these thoughts at times but, during his breakdowns, they took on terrifying proportions.” They troubled him so much he never slept in this room again until he was on his deathbed and only then when he was surrounded by the Turner paintings he loved.

Ruskin died at Brantwood on 20 January 1900 and was buried five days later in the churchyard at St Andrew’s Church in Coniston. Both the Celtic cross-style grave and the Ruskin Museum, founded in 1901 on the site of the former Mechanics’ Institute and Literary Society, were overseen by WG Collingwood, a former student of Ruskin at Oxford. Collingwood also acted as an assistant to Ruskin at Brantwood and wanted to honour his contribution to the Coniston community.

His artistic legacy survives among more dedicated followers too. “Ruskin, through his love of Turner, was fascinated by mountains. As an artist, my own infatuation with painting big rock faces can be traced back to Ruskin’s view of rock as a living substance,” says the Lake District artist Julian Heaton Cooper. “Ruskin has been somewhat overlooked but I hope, this year, we will come to consider him more kindly. He had vision, especially to foresee the fragile relationship between man and the planet we dwell on.” As Ruskin himself said: “To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion – all in one.”