Picnics in Britain: A history

So much more than merely dining alfresco, in Britain picnics offer an insight into the British psyche says Sally Coffey

Much like beach days in Britain, picnics don’t require a cloudless blue sky or guaranteed temperatures of over 25 degrees Celsius. No, all we really need is a hint of sunshine – even just a good bet of no rain – between the months of April and September and we’re good to go.

As soon as we’ve deemed the conditions are right, that’s it, we spring into action: digging out our hampers from underneath the stairs, diligently wrapping parcels of food in napkins or kitchen roll of placing them in Tupperware, and searching the house high and low for the ultimate accessory: the picnic blanket.

But how and when did the tradition of picnics take hold in Britain, and what are the essential ingredients for the perfect picnic? Here, I divulge all.

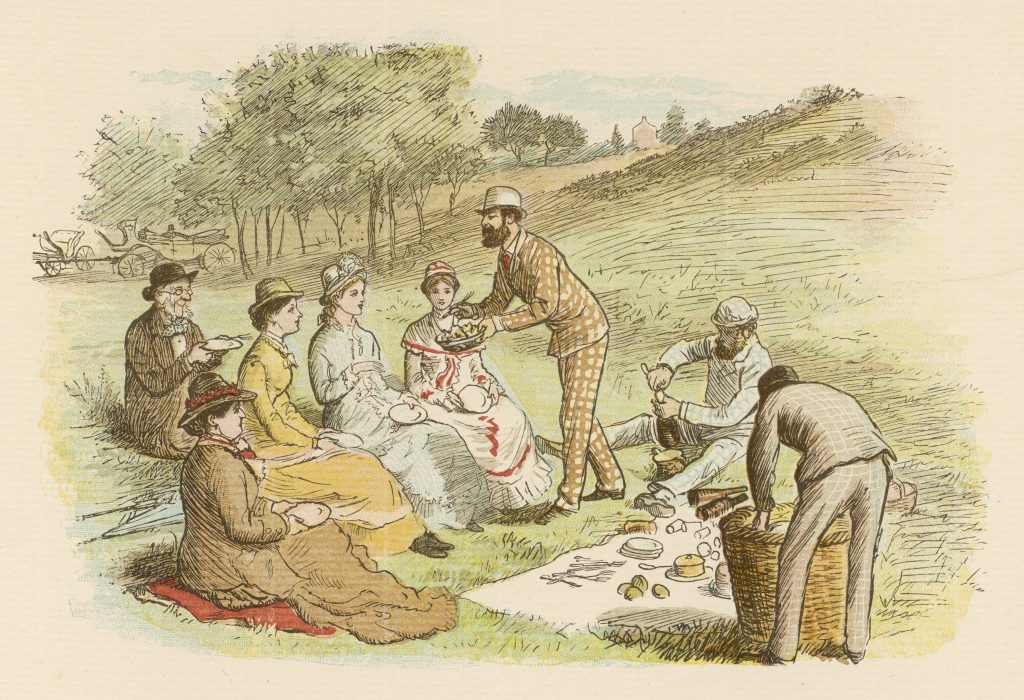

A drawing of a group of young ladies and gentlemen enjoying a picnic together in the

countryside, c.1880. Credit: Mary Evans Picture Library 2015

English writer W Somerset Maughan, may have pronounced that there “are few things so pleasant as a picnic lunch eaten in perfect comfort”, and picnics may feature in many English literary scenes, from The Wind in the Willows to any number of Enid Blyton or D H Lawrence books, but the truth is that we owe their existence – even their name – to the place of Maughan’s birth: France.

The term first appeared as the title of a rather gluttonous protagonist ‘Pique Nique’ in a French burlesque comedy, Les Charmans effects des barricades, ou l’amite durable de la compagnie des freres Bachiques de Pique-Nique, in 1649.

Whether it was in parlance before then we don’t know, but we do know that by the end of the 17th century the term ‘pique-nique’ was regularly being used by the French to refer to a way of eating in which each diner or guest would contribute to the meal in some way, either by bringing a dish or by paying towards the meal.

Throughout the 18th century, the popularity of picnics grew, though they were always held indoors and were the preserve of the aristocracy and members of high society – held initially in homes and later in restaurants, and they were often accompanied by entertainment, such as singing and dancing.

The French Revolution and the exodus of many French nationals, a large portion of whom fled to London, saw the pique nique cross the Channel.

In 1801, The Pic-Nic Society launched in London, which sounds a little like an early version of the Bullingdon Club and required each member to bring with them no fewer than six bottles of wine.

Soon the behaviour at these gatherings began drawing criticism, but despite picnickers being ridiculed in newspaper cartoons, picnics soon became popular with Britain’s upper classes, many of whom began adopting the picnic-style of eating in a new way by bringing picnics outside on their huge estates.

Whereas once they had been lively, lavish events that involved singing, dancing and a fair amount of debauchery, now picnics became more elegant, refined events, set in rural surroundings, which played well into the fashion for the cult of the picturesque.

By 1861, the picnic had become so popular among the upper and middle classes in Britain that Mrs Beeton dedicated a whole section on catering for a picnic for 40 people in her Book of Household Management, which shows that not much has changed in terms of the food we bring today compared to the Victorian era.

Then as in now, sandwiches featured heavily, as did cold cuts of meat, though today we’re more likely to pack a few slices of ham and some pre-cooked chicken drumsticks than the roast duck and roast fowl that Mrs Beeton recommended.

Drinks such as bottles of ale, ginger-beer, soda-water, and lemonade would still be welcome at a picnic today, though the brandy and sherry Mrs Beeton suggests is more likely to be replaced with Pimm’s or gin by today’s picknickers.

Another addition to a modern-day picnic that seems almost compulsory today is Scotch eggs, which have been around since at least 1738 when London department store Fortnum and Masons began selling them, though back then the egg would have been surrounded by fish paste instead of sausage meat.

Of course, what you pack in your picnic hamper rather depends on where you will be dining.

Having a park picnic with friends? Then reusable plastic cups and cutlery, a picnic rug, and a good selection of drinks and food to nibble or pick on will suffice. However, if you are planning a picnic for a smart outdoor event such as the Henley Royal Regatta or Glyndebourne, you will probably want to reassess what you pack in your hamper.

Advice from Debrett’s, that all round guardian of etiquette, suggests that for a picnic at Glyndebourne one should prepare for a grander affair: “British summer classics, such as smoked salmon, asparagus and strawberries are popular choices,” it says, adding that “real cutlery, linen napkins and glasses are the norm, along with a bottle of chilled bubbly.” Or ‘Champagne à discrétion’ as Mrs Beeton would say.

Wherever you choose to picnic, soak it up and enjoy the feeling of being outdoors, because in Britain, you never know when you might be able to do it again and it’s that sense of now or never, which makes us love picnics ever so.

Read more: