A merry berry Christmas: The history of the mistletoe tradition

Mistletoe hung above the door is often seen as an invitation for a Christmas. kiss, but the plant has a long history, as Lara Dunn discovers. Here we explore the origins of the mistletoe tradition…

The mistletoe tradition

There’s something strange and almost mystical about mistletoe, even before you start digging into its past.

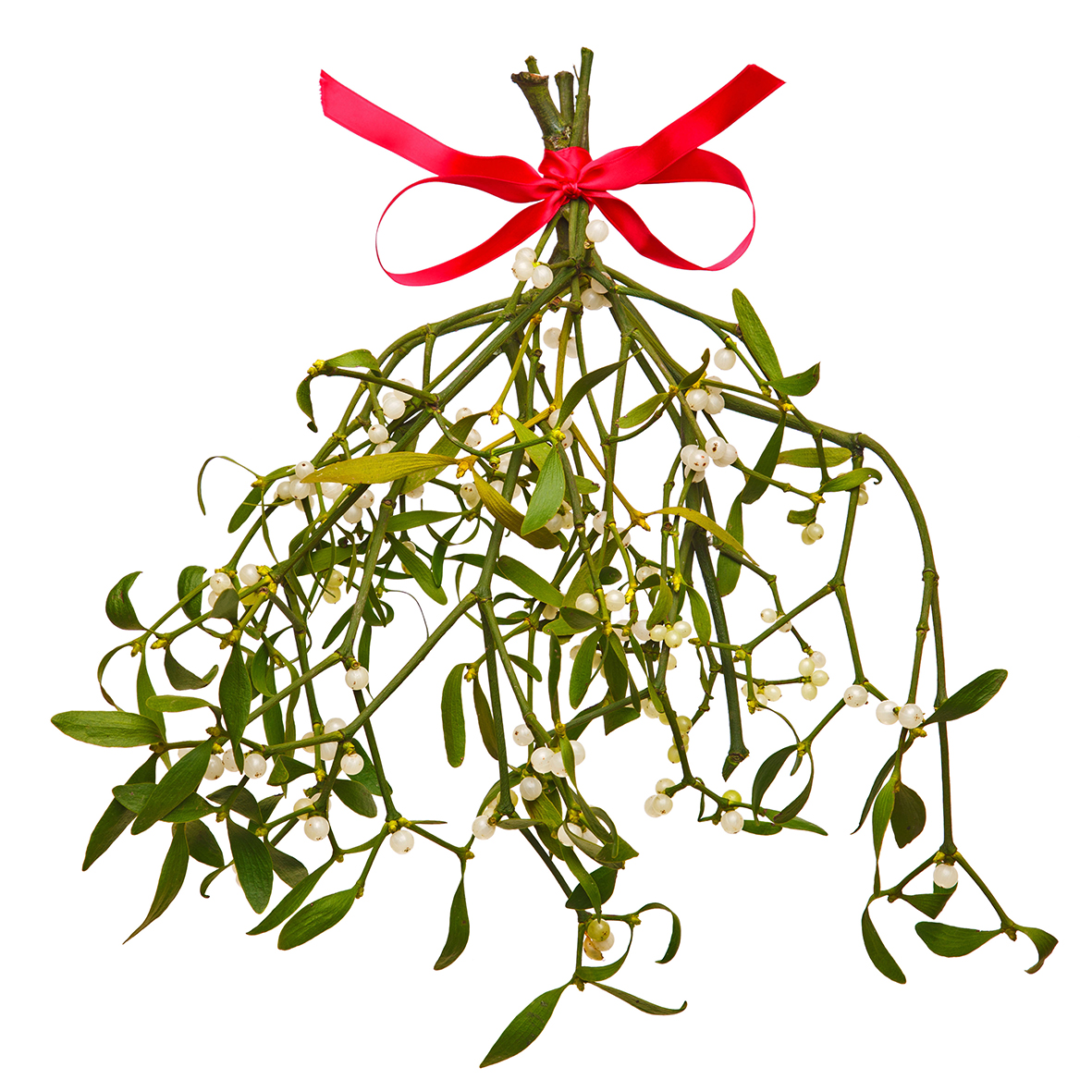

It’s hemiparasitic, meaning it draws resources from a host plant but also has chlorophyll, so can photosynthesise to create nutrients. The species of mistletoe native to the British Isles is Viscum album, or European mistletoe, which grows in the boughs of deciduous trees, most commonly apple, hawthorn, and poplar.

It’s a widespread sight in traditionally orchard-rich areas of Britain, such as Worcestershire, Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, and Somerset, cheering the appearance of winter-grey trees with its bright green globes of foliage. With seeds spread from tree to tree in the droppings of birds, the plant grows with no tether to the ground below, but is attached instead to the host tree by a root-like tendril called a haustorium, through which it extracts water and nutrients.

As with many of Britain’s most colourful festive traditions, the practice of hanging mistletoe in the home at Christmas almost certainly owes its origins to the Victorian love of taking a Celtic tradition and embellishing it.

However, the roots of mistletoe traditions are as complex as the plant itself.

The ability to live suspended above the ground may well have contributed to some of the generous quantities of mythology surrounding mistletoe, as might its verdure and fruitfulness in the depths of winter. Whatever the cause, mistletoe is mentioned as far back as both Druidic and Norse lore.

Pliny the Elder mentions Druidic rituals concerning mistletoe in his Natural History in the 1st century AD. Pliny’s writings stated that for the Druids, mistletoe growing on oak was regarded to be the most sacred, with its harvest requiring intricate rituals involving cutting the bough with a golden sickle and catching it in a cloak before it touched the ground.

The sacrifice of two white bulls was also mentioned as a crucial part of the ritual.

The plant was often given as a drink to help fertility in both humans and animals and was believed to be a powerful antidote to poisons; ironic considering its own toxic nature. It’s unknown how accurate Pliny’s Natural History account of the mistletoe harvest is, but much of the information is supported by documentation of similar practices in other Celtic ceremonies.

Norse mythology mentions mistletoe in the story of the goddess Frigg, first wife of Odin, associated with marriage, prophecy, motherhood, and clairvoyance, and for whom the day Friday is named.

The story goes that Frigg dreamt of the death of her son Balder – god of light – and demanded that all living things swear to do him no harm.

For reasons unclear, but maybe due to the aerial nature of the plant’s growth, mistletoe was missed from the list.

Loki, the god of mischief, noticed this and created a spear from the plant that was given to Balder’s blind brother, Hoder. Hoder joined in a game of throwing objects at the invincible Balder, accidentally killing him with the mistletoe spear.

The death of the god of light brought about the long darkness of the northern winter and the tears of mourning shed by Frigg at the loss of her son transformed into glistening white berries on the mistletoe. Frigg decreed that never again would the plant result in harm and would instead promote love and peace. Even two warriors passing accidentally beneath it should kiss, lay down their weapons and set aside their dispute.

This tale, combined with the plant’s reputed fertility benefits, probably led to the mistletoe tradition of it eventually being adopted as a popular decoration during the festive season, hung to invite peace and prosperity – and presumably fertility – into the home, while keeping away less desirable influences.

Now, an etiquette has grown for mistletoe kissing. A man can only kiss a woman on the cheek and for each kiss, a berry must be removed from the mistletoe bough. Once all the berries are gone, the kissing must stop.

Today, the bright green plants and white berries of mistletoe remain very much a part of our Christmas tradition, as well as an attractive feature of the rural landscape of the west of England. Thankfully, by and large, the bulls are now safe.

Did you know?

Despite its inherent toxicity to humans, mistletoe has long been explored for its medicinal properties. In early use it was thought to enhance fertility, perhaps in part due to its miraculous-seeming growth in the depths of winter. The plant does in fact contain substances very similar to the female reproductive hormone progesterone. It was also believed to be efficacious against poisons, ulcers and even epilepsy.

Modern medical exploration and research includes working with mistletoe as a support drug in the treatment of cancer.

This is an extract, read the full feature in our December 2023/January 2024 issue of Discover Britain, available to buy here.