Great British romances

Despite the buttoned-up stereotype, Britons are responsible for some of the world’s greatest love affairs in history. Martha Alexander presents her top six, for better or for worse

Henry VIII & Anne Boleyn

Whether defined by anguished love letters or record-breaking diamonds, marriage or chastity, politics or poetry, the British in love are not easily pigeon-holed. In fact, our nation’s greatest romances have little in common with one another – except that most didn’t end happily ever after, as childhood fairy tales promise.

Take Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, for example. Not many of the world’s all-time greatest love stories end with one half of the couple ordering the beheading of the other on charges of witchcraft, incest and adultery but then again, Henry VIII’s second marriage was no normal love story. After all, it is rare that a woman ends up marrying their sister’s ex-boyfriend.

It was Mary Boleyn who first became Henry’s mistress, yet it was Anne who he married, having decided that she was not “ruined” like her elder sister. Anne was also schooled in France and fluent in French – a major USP at the time – so attracted a coterie of suitors when she arrived at the English court. Such things served as a red rag to the bullish Henry. He saw Anne as sophisticated, popular and witty, and he believed her refined continental ways might help improve his own cultural capital.

That Anne was in love with someone else – Henry Percy, the 6th Earl of Northumberland – was not a problem for Henry, who ordered the termination of that engagement. Rather than propose marriage, he offered Anne the role of his official mistress. She shrewdly refused; mistresses did not become Queens, after all. This show of resistance and self-worth only inflamed the king’s already white-hot ardour and he duly proposed marriage.

All wasn’t smooth sailing. Let’s not forget that Henry already had a wife, Catherine of Aragon, albeit one who had “failed” to give him a son. Divorce was not an option, and so the king appointed himself head of the Church in England in 1534 and declared his first marriage invalid. Henry literally decimated the religious order of his country for Anne – that’s how deep his feelings ran.

Yet Henry’s fickleness soon returned. Anne would talk back to him and suffered three miscarriages while trying for a son. All the things that once attracted him began to disgust him. He sought a more straightforward, deferential woman, while also convicting Anne of high treason.

Ten days after she was beheaded in 1536, Henry married Jane Seymour. Yet despite a further three wives, it was Anne that he loved madly in a way that made him feel out of control – which is more than can be said for his other wives.

Elizabeth Taylor & Richard Burton

He described her as “a true miracle of construction”; she called him “magnificent in every sense of the word”. That Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor married and divorced twice is testimony to their fiery, destructive love.

Theirs was an enduringly fascinating partnership. She, a child star who grew up on sprawling English estates and he, from a Welsh mining town. They met officially on the set of Cleopatra in Rome, 1963, and an off-screen union was inevitable. Their screen kisses lasted much longer than the takes required and the following year they were married. Burton bought Taylor enormous diamonds; on a whim, she picked a Picasso up on Bond Street as a gift for him. Together they amassed Rolls-Royces, a jet, a yacht and property all over the world, including a house in the Hertfordshire countryside. They may as well have called London’s Dorchester Hotel “home”, given the amount of time they spent there. The Harlequin Suite still has a pink marble bathroom installed at Taylor’s request.

This might be the stuff of capitalist fairy tale, but it is also where their marriage seemed to hit the buffers: the relationship seemed to live and die on drama.

Burton wrote to Taylor constantly – even when they were in the same house. Everything, it seemed, had to be passionate or else it was void. Films such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The Taming of the Shrew exploited the natural fireworks between them. Taylor coped with fame better than her husband, who became paranoid and insecure. Added to that, his philandering was compulsive, frequent and involved women that his wife knew. Humiliated, she filed for divorce in 1974.

Within a year, they were remarried with Elizabeth writing that the pair were “stuck like chicken feathers to tar… I know the best is yet to be!” Sadly, what was to be was the same old story: drinking, fighting, jealousy and infidelity reigned. A second divorce came in 1976. However, Taylor maintained Burton continued to write to her up until his death in 1984 and for her part admitted, “In my heart, I will always believe we would have been married a third and final time… From those first moments in Rome we were always madly and powerfully in love.”

Virginia Woolf & Vita Sackville-West

The romance between Bloomsbury Group writers Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West was not an illicit or scandalous affair. Although it happened some 100 years ago, it didn’t precipitate much pearl clutching: the two women’s husbands knew of the affair and barely blinked an eye. Vita’s husband Harold was bisexual and they were all part of a bohemian circle with liberal values.

The decade-long relationship was lustful and loving, as evidenced in diaries and letters. Vita, younger by ten years, was more impassioned and given to infatuation. “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia,” she wrote. On other occasions she reported that she had “rarely taken such a fancy to anyone” and that Virginia was “as delicious as ever”.

Yet despite this clear admiration, Virginia was insecure. She had complex but delicate mental health issues that made her cautious with Vita, and she also felt less beautiful than her lover, who often strayed. Virginia variously described Vita as a “real woman”, one “in full sail on the high tides” who brimmed with confidence and competence. Vita’s flair for making things beautiful supports this: just one look at the legacy left at her former Kent home, Sissinghurst Castle, with its famous gardens, reveals plenty about the woman who bewitched Woolf.

Vita in turn inspired Virginia to write Orlando, her 1928 novel which was ahead of its time in terms of its treatment of gender and same-sex relationships. Orlando’s protagonist changes sex, lives for hundreds of years and encounters British historical figures, yet it remains, at its heart, a love letter on an epic scale.

John Keats & Fanny Brawne

“I cannot exist without you… Love is my religion – I could die for that – I could die for you.” It’s hard to believe that words of such infatuation could be written by a man who had, only a year earlier, famously made a very public case for a life of uncomplicated bachelorhood. Yet such was the power of the love that John Keats had for Fanny Brawne.

The couple met as neighbours in London’s Hampstead. Fanny was fashionable and fiery, with remarkable blue eyes. Above all, it was the 18-year-old’s kindness that first attracted Keats to her: she proved to be a sympathetic ear for the fledgling Romantic poet who was grieving the death of his brother. He fell completely in love.

Keats House is now a museum and the engagement ring he gave Fanny in 1819 is on display, significant because its purpose changed from marking a betrothal, to marking a loss. Three years into their engagement, Keats died of tuberculosis aged just 25. He was buried with Fanny’s unopened letters. Despite later re-marrying, she mourned Keats for six years and wore his ring until her death.

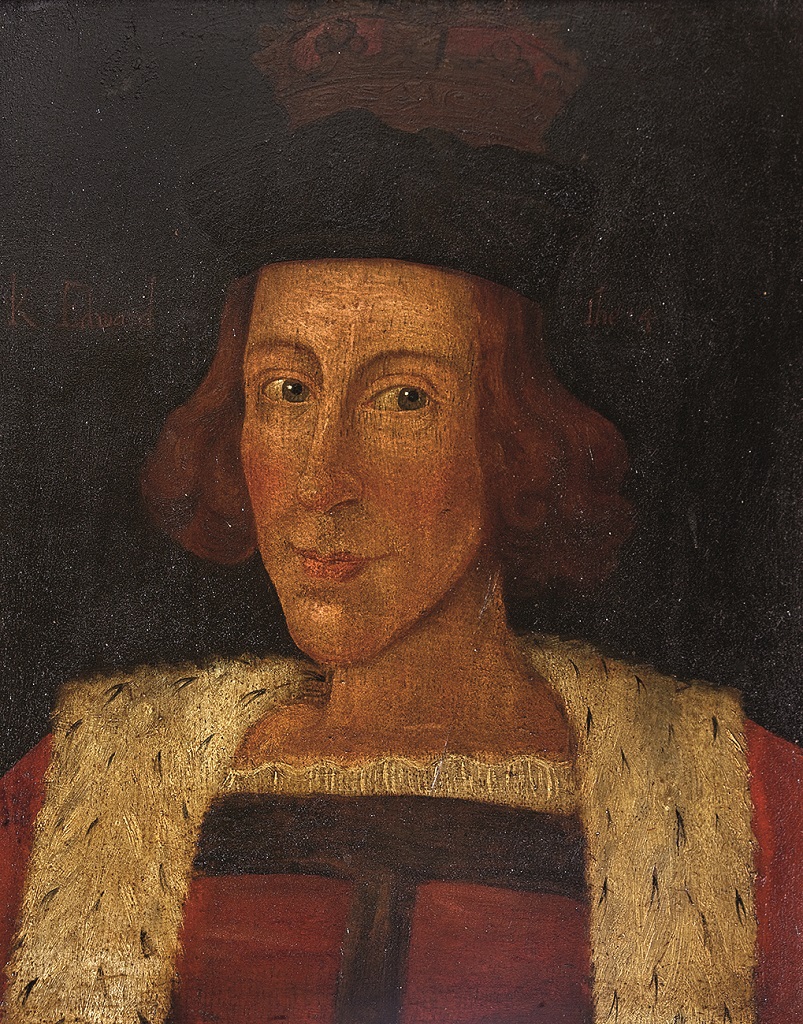

Edward IV & Elizabeth Woodville

The 19-year marriage between Elizabeth Woodville and Edward Plantagenet was a scandalous union, set against the backdrop of the Wars of the Roses, the 30-year civil war between the Houses of Lancaster and York that began in 1455.

In 1461, Elizabeth lost her first husband, the Lancastrian knight Sir John Groby, in battle – and this meant she lost her home and her children’s inheritance too. Legend dictates that the widow waited under an oak tree on a route upon which she knew the king was riding. As Edward approached, she begged him to restore her children’s inheritance. Her considerable beauty blindsided the young Yorkist king: it was love at first sight.

They wed in secret, crushing the possibility of the king marrying anyone with better status that might have proven a powerful diplomatic or political tool. That this was a love match infuriated courtiers who had tried to marry Edward off to a French princess, while the king’s mother thought Elizabeth common.

The new queen fascinated her subjects; they loved to speculate about her motives – and her background. A rumour did the rounds that Elizabeth was descended from a water goddess with magical powers until people genuinely believed she had bewitched the king with a potent love spell.

The couple remained happy until Edward’s rather sudden death in 1483, after which Elizabeth had more battles to fight. That she won them, ultimately arranging the marriage between Henry Tudor and her own daughter Elizabeth of York that ended the War of the Roses, was a perfect way to honour her late husband’s memory.

Queen Elizabeth I & Robert Dudley

Many are surprised to learn that Elizabeth Tudor’s famous nickname – “The Virgin Queen” – might not have been entirely accurate. It’s true that the Tudor monarch never married. Her father Henry VIII’s six attempts can hardly have done much to recommend the tradition and besides, Elizabeth felt deeply that being a married woman would impede her role as ruler.

Yet this didn’t mean she wasn’t capable of being the heroine of her own love story. Her relationship with Robert Dudley was the subject of plenty of court gossip. To this day, the truth remains murky.

Born a year apart, Dudley and Elizabeth were childhood friends and he proved a loyal constant throughout their lives. He was Elizabeth’s “favourite” – the moment she became Queen, she appointed him as her Master of Horse – in charge of the travels of the court. She called him her “little dog” and her “Bonny Sweet Robin”, which would possibly be emasculating if handsome Dudley hadn’t inspired such blatant lust in Elizabeth. And the feeling was mutual.

They were rarely apart, leading to an uptick in rumours that included tales of jealousy, bed hopping and even a hidden pregnancy. While this sort of thing was hardly shocking, now or then – the Tudors were a boldly libidinous lot – it’s a shame that convention prevented Elizabeth from being both publicly in love and the ruler of an empire. After Dudley’s death in 1588, the queen’s grief was absolute, and she kept his last letter to her by her bedside for the rest of her life.

Until the end, Elizabeth swore that they had never been lovers, yet there is no doubt Her Majesty had been very much in love.