Light in the Dark: Florence Nightingale’s legacy

More than just the “Lady with the Lamp”, Florence Nightingale was a Victorian pioneer who saved the lives of countless people. As her 200th anniversary approaches, Diana Wright explores the famous Briton’s legacy

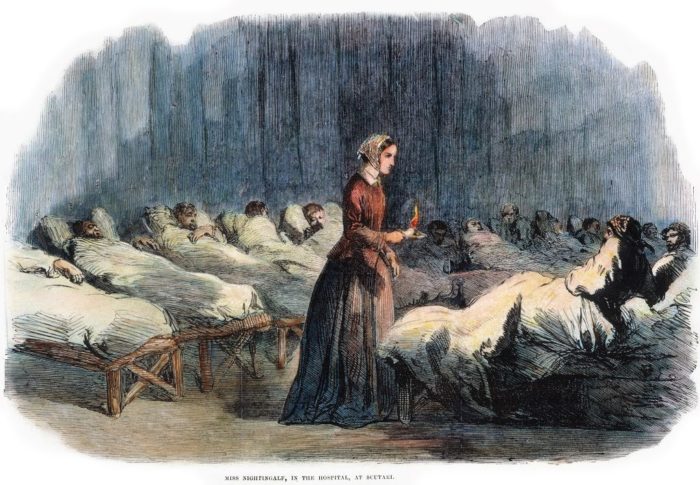

On 24 February 1855 an artist’s engraving was reproduced in the Illustrated London News that captured the public imagination. It showed Florence Nightingale, the “Lady with the Lamp”, tending to stricken soldiers of the Crimean War. Newspapers like The Times quickly took up the theme: “She is a ‘ministering angel’ without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her… with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds.” Songs and poems sang Florence’s praises as Nightingale-mania swept across the country. Yet the iconic Lady with the Lamp image was to overshadow so much else that Florence did in a long career that broke with social expectations, as she pioneered nursing and training as well as hospital reform. As we celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Lady’s birth this year, it’s time to shine the lamp on her wider work and legacy.

Named after the Italian city where she was born on 12 May 1820 – her parents, William and Fanny, were on a Grand Tour – Florence received a privileged upbringing on the family’s English country estates at Lea Hurst, Derbyshire and Embley, Hampshire, with an extensive home education from her father interspersed by continental travel. She was clearly gifted and, as her elder sister Frances Parthenope noted “worked patiently to the pith and marrow of every subject”; mathematics in particular was her passion.

From an early age Florence also wrestled with religious matters and, on 7 February 1837, she recorded, “God spoke to me and called me to His Service.” Already imbued with a strong sense of moral duty – she regularly visited the poor and sick – she nurtured a growing belief that nursing was to be her vocation.

Florence’s parents opposed any such idea: nursing was considered the work of lowly, poor people and was beset by negative images of drunken, loose behaviour. Upper middle-class women were expected to marry well, a prospect of genteel domesticity that filled Florence with a horrified sense of pointlessness, as revealed by her novel-turned-essay, Cassandra, published much later. Tall, slender, eligible; she attracted at least one marriage proposal but declined. “I have no desire now but to die,” she noted on 30 December 1850.

In the end Florence’s determination won through and, in 1851, her parents allowed her to undertake three months’ nursing training at an inspirational hospital and school in Kaiserswerth, Germany. Two years later, aged 33, she honed her administrative skills as superintendent of the Establishment for Gentlewomen during Illness in London’s Harley Street.

In the wider world, Britain was becoming embroiled in the Crimean War against Russia and Florence, like

the public at large, was shocked by newspaper reports of appalling conditions in British army hospitals.

When Sidney Herbert, a friend and Secretary at War (a government position in charge of the War Office), asked her to oversee the introduction of female nurses into military hospitals in Turkey she needed no second bidding.

In November 1854, Florence arrived with 38 nurses at Scutari near Constantinople (now Istanbul) to discover a vermin-ridden hospital lacking even in basic equipment, and more soldiers suffering from disease and dysentery than battle wounds. While many male army doctors resented her and her nurses, they were so over-stretched that they accepted help.

For her part, Florence could be prickly with anyone who hindered her, but progress was soon made as she procured linen and other supplies, and set nurses to work cleaning the hospital and ensuring the soldiers were properly fed and clothed. “I am really cook, house-keeper, scavenger… washerwoman, general dealer, store-keeper,” Florence reported to Herbert, while by night she became the “Lady with the Lamp”. A Sanitary Commission sent out from England repaired the sewers over which the hospital sat, ventilation was improved, and mortality rates dropped.

In 1855 Queen Victoria awarded Florence a jewelled brooch, designed by Prince Albert, “for her devotion towards the Queen’s brave soldiers”. At the end of the Crimean War in 1856, an exhausted Florence returned to England a national heroine.

By now Florence’s parents were proud of their daughter’s vocation and Parthenope (as she was known), who had earlier struggled to accept her sister’s hard-won independence, revelled in dealing with the mountains of adulatory letters. By contrast, Florence dismissed the “buz-fuz” around her name but was quick to put “Nightingale Power” to good use, setting herself up in London’s Burlington Hotel – nicknamed the ‘Little War Office’ – as the

great and the good came to speak with her.

Haunted by the terrible loss of soldiers’ lives in the East – in January 1855 alone more than 2,700 died from preventable diseases spread by poor sanitation compared with around 83 who died from battle wounds – Florence worked behind the scenes to influence a Royal Commission into army healthcare: marshalling complex statistics on the causes of mortality and sanitary solutions into attention-grabbing “rose diagram” form (similar to pie charts) “to affect thro’ the Eyes what we may fail to convey to the brains of the public thro’ their word-proof ears”. In light of her work, army healthcare was overhauled.

She later investigated the welfare of British soldiers in India for an official report that urged sanitary, economic and agricultural reform for the country as a whole.Over the next five decades of her long life, Florence campaigned relentlessly to reform nursing practice and hospitals, championing ideas that have influenced modern healthcare to this day. She published more than 200 books, reports and pamphlets, most famously 1859’s Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not with its timeless principles, not least that prevention is better than cure.

From the same year, Notes on Hospitals set out how the design of buildings, including good ventilation, affects patient recovery. Florence’s greatest achievement lies in transforming nursing into a respectable profession for women and in 1860, using money from the Nightingale Fund raised by well-wishers, she set up the Nightingale Training School at London’s St Thomas’ Hospital. Its nurses took her ideas to hospitals across the country and indeed the world.

It is ironic that throughout her years of campaigning Florence was often bedridden due to ill health – she probably contracted chronic brucellosis in the Crimea, a bacterial infection causing fever, depression and debilitating pain – yet she worked on from her sickbed. She urged the introduction of trained nurses into workhouses, established a specialist School of Midwifery at King’s College Hospital, encouraged district nursing and promoted preventative healthcare to ordinary folk in their homes. Mellower in later life, she also enjoyed visits to Parthenope and her family at Claydon House in Buckinghamshire, which is now a National Trust property. Far from her early anxieties over an existence with no purpose, Florence wrote on her 75th birthday: “There is so much to live for.”

In 1858, Florence was the first woman elected to the Royal Statistical Society, in 1883 she was the first person to be awarded the Royal Red Cross for exceptional services in military nursing, and in 1907 she became the first woman to receive the Order of Merit, Britain’s highest civilian decoration. When she died on 13 August 1910 at the age of 90, she was buried, as she had wished, in the family plot at St Margaret’s Church, East Wellow in Hampshire.

Two hundred years after her birth, however, her influence lives on: through the Nightingale Medal awarded by the International Red Cross to exceptional nurses, through the Florence Nightingale Foundation, and the Florence Nightingale Museum at St Thomas’ Hospital.

This year, a Florence Nightingale commemorative service was due to take place on her 200th birthday on 12 May at Westminster Abbey. This has now been cancelled, but the exhibition at The Florence Nightingale Museum, Nightingale in 200 Objects, People & Places, is available to view online. Her biggest legacy lives on, however, through the wonders of modern nursing.