Discover London’s criminal history

Crime has played a huge role in London’s history and, when you start looking, it is quite remarkable to see just how many reminders and artefacts remain, left by the good, the bad and the totally barking mad… We look at London’s criminal history

Some Londoners decide to become criminals out of choice, such as Soho mobster Billy ‘boss of the underworld’ Hill (1911-84), founder of the ‘project’ in 1952 – the carefully planned heist, who retired from crime a rich man after robbing a fortune in cash from just one Post Office van.

Others become agents of justice – like Albert Pierrepoint (1905-92) and John Ellis (1874-1932), two of London’s last executioners, who hanged dozens of young men and women between them, from serial killers to seductresses.

Others become crime-fighting pioneers, such as the author Henry Fielding (1707-54), who switched from a failing career as a playwright to found the world famous Bow Street Runners in 1749.

Then there are the psychopaths – those who are born bad – like Jack the Ripper. It’s 125 years since Jack terrorised the East End of London when he murdered five women (some say the true figure is much higher) in a fit of bloodlust yet to be matched.

Here’s a look at some of the infamous chancers, psychos and criminal careerists that have terrorised London over the centuries…

Jack the Ripper

In 1888 Whitechapel was a maze of poverty and vice. It was here that the world’s most famous serial killer operated. Preying on female prostitutes, ‘he’ committed at least five murders in the autumn of 1888 – although some ‘Ripperologists’ have claimed the Ripper took many more victims over a longer period of time.

What is undeniable is that the Ripper has inspired miles of newspaper print, libraries of fiction and non-fiction, and hours of documentaries, television dramas and movies all devoted to answering the question: Who was Jack the Ripper?

A definitive answer is almost certainly lost to history. Thankfully, though, many structures from his world still survive and Jack-the-Ripper related buildings are visible from the moment you step out of Whitechapel Underground station into Whitechapel High Street and the market.

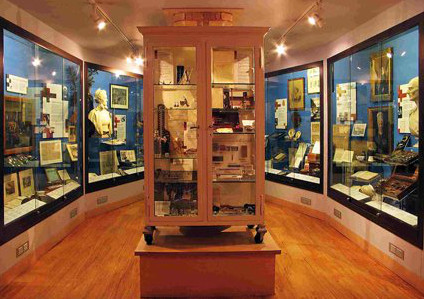

The Working Lads Institute next door to the station was where inquests of some of the Ripper’s victims were held. The Royal London Hospital Museum, housed in the former crypt of St Philip’s Church (entrance in Newark Street, to the rear of the Royal London Hospital, opposite the station) is open Tuesday-Friday from 10am to 4.30pm and it’s worth a visit to see the so-called Openshaw Letter, allegedly written by Jack the Ripper himself. Although many claim the letter was a fake, sent by an enterprising journalist to whip up excitement, it remains a fascinating and tangible link to the time of the murders.

The Kray Twins

Born into poverty in the East End, Ronald ‘Ronnie’ and Reginald ‘Reggie’ Kray began their violent careers by running several protection rackets from their base, a run-down local snooker club. They were soon involved in hijacking and armed robbery and used stolen cash to buy clubs, pubs and houses.

The Krays’ notoriety helped bring them into contact with some of the era’s biggest political and show business names, turning them into celebrities of a sort. Friends included the artist Francis Bacon, Tory peer Lord Boothby and actress Barbara Windsor.

By the mid-60s Ronnie and Reg Kray were of great concern to police and government alike. ‘The Firm’, as their gang was known, was more than a loose, rag-tag group of criminals; members were loyal and prepared to do anything to advance the Firm’s aims.

Worst of all, as far as the authorities were concerned, they were well organised. It looked as though the Krays’ criminal network could last for generations. Fortunately, because Ronnie was as mad as a box of frogs, with Reggie not far behind, Scotland Yard’s job was eventually made easier than it might have been and both brothers were put behind bars after being convicted of the savage murder of Jack ‘the Hat’ McVitie. Sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment both men died in jail. Ronnie died of a heart attack in Broadmoor on 17 March 1995. Reggie died from bladder cancer on 1 October 2000, aged 66.

One great London location with links to the Krays is the Carpenters Arms in Cheshire Street in 1967. Ronnie and Reggie were drinking here on the night of 28 October 1967, shortly before McVitie was murdered. By the time Reggie was finished with him McVitie was so cut up, his liver slid out from his body.

Now a small, cosy and only slightly fashionable pub, serving around 50 different ales, the bar counter (originally put in by the Krays) is said to have been made from coffin lids.

Patrick Mahon: The Butcher of Eastbourne

In 1924, Patrick Mahon’s wife became so concerned about her husband’s constant disappearances that – suspecting the 35-year-old handsome salesman was having an affair- she decided to search through his things.

She found a ticket for Waterloo’s left luggage office in his suit pocket and collected a small leather bag. Inside she found a pair of knickers, a blue scarf, two pieces of white silk and a knife – all covered in blood. Detectives questioned Mahon and he eventually led them to an isolated Eastbourne bungalow where they found he had used it as a butcher’s shop – of human flesh.

They sent for eminent London pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1877-1947) who, during this case, came up with the idea to use a standardised field kit, a major development in police forensics. It was christened the Murder Bag and contained rubber gloves, tweezers, evidence bags, magnifying glass, compass, ruler and swabs.

Inside the house, Spilsbury found two large saucepans of boiled flesh, more flesh in a hatbox, a biscuit tin stuffed full of human organs and a trunk containing pieces of torso. Spilsbury also discovered that the victim had been pregnant.

At his Old Bailey trial Mahon admitted that his mistress, Emily Kaye, had died at the house, but claimed she had fallen and hit her head during a quarrel. He failed to convince the jury and Mahon was hanged on 3 September 1924.

You can visit the public galleries of the Old Bailey – the country’s most famous law courts – for free, they are open each day for viewing of trials in session.

Thomas Neill Cream: The Lambeth Poisoner

The victims of the Lambeth Poisoner, who struck between 1889 and 1891 included 19-year-old Ellen ‘Nellie’ Donworth, 27-year-old prostitute Matilda Clover and Alice Marsh (21) and Emma Shrivell (18), who both died in agony in the flat they shared.

In 1891, a London doctor, Thomas Neill Cream (1850–92), met a policeman from New York City who was visiting London. The policeman mentioned that he had heard of the Lambeth Poisoner, and Cream filled him in with so many details he grew suspicious and reported Cream to a British policeman.

Scotland Yard put him under surveillance and soon found that Dr Cream, of 103 Lambeth Palace Road (today this is the site of the entrance to St Thomas’s Hospital medical school), liked to consort with the prostitutes of Lambeth.

When detectives arrested Cream at his home, they spotted a bottle full of strychnine pills – the method by which the victims had died. As he was arrested the doctor said: ‘You have got the wrong man; fire away!’

Cream was convicted and sentenced to death. Dr Thomas Neill Cream was hanged on the gallows at Newgate prison (today the site of the Old Bailey) on 15 November 1892.

The hangman claimed that Cream’s last words were ‘I am Jack the –’ but it was established that Cream was in a US prison at the time of the Whitechapel murders.

Today you can take one of the most scenic strolls near Cream’s former home, along the Albert Embankment starting from St Thomas’s Hospital. There are spectacular views of Parliament to the north, while to the south are the Victorian gardens of the old Lambeth Hospital. Keep an eye out for the weathered statue Sir Robert Clayton (1629-1707) a former Lord Mayor of London, which Cream would have passed every time he walked to work from his house.

Captain Blood: The Boldest Robbery

In 1671 Irishman Colonel Blood tried to steal the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London after befriending the keeper and his family – suggesting their daughter might marry his wealthy nephew.

On 9 May, Blood arrived with his ‘nephew’ and some friends and was let into the Tower. He knocked out the keeper with a mallet, grabbed the crown and flattened it with said mallet before stuffing it down his trousers – turning it into a magisterial codpiece.

The keeper quickly regained consciousness and began to shout, ‘Murder, Treason!’ Blood and his accomplices scarpered, but he was arrested by the Iron-Gate, after trying to shoot one of the guards.

In custody, Blood stubbornly demanded: ‘I’ll answer to none but the King himself.’ He knew the monarch had a reputation for liking bold scoundrels and when he was finally brought before King Charles II, Blood told him that the Crown Jewels were not worth the £100,000 they were valued at, but only £6,000. Charles was highly amused.

The King then asked Blood, ‘What if I should give you your life?’

‘I would endeavour to deserve it, Sire!’ Blood replied. Not only was Blood pardoned, the King gave him Irish lands worth £500 a year. Blood became a familiar figure around London and made frequent appearances at Court until his surprisingly mundane death from an illness in 1680.

British monarchs have used the 18-acre area on which the Tower of London is built for almost a thousand years. The Krays were imprisoned here for a couple of weeks in 1952, after beating up their sergeant during their National Service. Visitors should aim to arrive early to be able to take in the full experience.

Patrick Thomas: The World’s Biggest Mugging

Bearer Bonds, cheques drawn mainly from banks and the government, are used to transfer huge sums of money. They all contain the legend: “promise to pay the bearer on demand”, and can be treated just like cash.

In 1990, an estimated £30billion was carried in bearer bonds by messengers (mostly elderly men, all unarmed and unescorted) to and fro across London’s Square Mile each day.

On 2 May 1990, John Goddard, a 58-year-old messenger with money broker Sheppards, left the Bank of England with £300m in bearer bonds in a briefcase. As he turned into Nicholas Lane (which runs between Lombard Street and King William Street) a man in his late twenties stepped out from the shadows, placed a knife against Goddard’s throat and relieved him of his briefcase.

The City of London Police, based in nearby Wood Street (where there’s a small, free and fascinating museum), pulled out all the stops to find the knifeman and quickly found that the mugging had been planned to the last detail by an international criminal network.

After Mark Osborne, a Texan businessman, attempted to sell some of the bonds to an undercover FBI operative in New York he was arrested, ‘turned’ and used to trap other members of the gang. Osborne’s body was later found in the boot of a car with two bullets in his head.

Detectives eventually tracked down all but £2m of the £292m. Police believe the City mugging was carried out by Patrick Thomas, a petty crook from South London. Thomas too was found dead from a gunshot wound to the head in December 1991, before he could be charged.

The Bank of England Museum is open Mon-Fri 10am–5pm, admission free.

Kris Hollington is the author of Criminal London: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Capital of Crime, published by Aurum, £10.99