Lest we forget: meet the First World War Victoria Cross heroes

Remembrance Day on 11 November never fails to move. The incomprehensibly long list of those who valiantly fought and gave their lives for their country is endlessly poignant, and the sombre, quiet dignity of the ceremony befits their sacrifice. For those who wish to learn more about the stories behind those names on the cenotaph – 956,000 brave British serviceman lost their lives during World War I – a new book tells the story of the 628 distinguished soldiers who were awarded the Victoria Cross for valour, the highest accolade, open to all ranks, a quarter of whose recipients were bestowed the medal posthumously. Victoria Cross Heroes of World War One by Robert Hamilton makes humbling reading – here, Hamilton introduces the book, and we meet just three of the heroes to whom we owe so much.

When the design of what would become the most highly prized military honour was being finalised, the monarch who lent her name to it personally intervened on the matter of the inscription. Queen Victoria rejected “For the Brave”, an early proposal, in favour of “For Valour”. The thought process behind the change goes to the heart of what the Victoria Cross stands for. Bravery was not the exclusive preserve of the decorated: all soldiers who went into battle were worthy of that epithet. Valour, on the other hand, carried connotations of the exceptional. Victoria Cross winners were a rare breed, men for whom the diligent discharging of duty was never enough; men who grew in stature when faced with battlefield conditions that might cause others to shrink; men who could look death nervelessly in the eye; men whose only thought was to advance when a backward step might have been the judicious course.The gallant exploits of such individuals are documented within these pages, stories of daring and courage, selflessness and sacrifice; stories that are a humbling testament to the finest qualities of the human spirit.

Almost half of all Victoria Crosses awarded since the pre-eminent honour was instituted in 1856 went to men who fought in the Great War: 628 acts of heroism, with disregard of personal safety a running theme. Captain Noel Chavasse’s contempt for danger earned him two Crosses in as many years, one of only three men to add a Bar to the VC ribbon. He didn’t live to receive the second, his luck running out at the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917. Chavasse’s family at least had the comfort of an amendment to the Royal Warrant that enabled the VC to be awarded posthumously. One in four recipients did not survive to have the medal, so valiantly earned, pinned on their uniform.

Heroism comes in many flavours. The image of a gung-ho individual assault on an enemy position readily springs to mind, and indeed numerous instances of such odds-defying solo raids are recounted. Aerial dogfights were also by their very nature solitary pursuits, pilots such as Albert Ball and Mick Mannock having to contend with flimsy, often unreliable machinery as well as withering fire. But there were joint enterprises too, where gallantry and the group were indivisible. The crew of the “Mystery” ships, that used themselves as human bait to lure U-boats into their net, operated as a collective and were exposed to the same threat. Seaman William Williams was a member of one such team; his VC came courtesy of the ballot system, where fortunate individuals were honoured on behalf of a larger cohort. On land, at sea and in the air, servicemen from disparate backgrounds showed fortitude and resolve that set them apart. VC winners were invariably self-effacing, uncomfortable in the spotlight. “I only did my job,” said William Leefe Robinson after downing the first enemy airship over British soil, an episode that brought him the kind of attention reserved for rock stars today; celebrity that sat awkwardly with the unassuming airman.

Combat was no prerequisite for the highest military honour, no determinant of a man’s courage. Doctors – such as Chavasse – faced the same mortal dangers as rifle-wielding infantrymen as they strove to save lives. Pipers, sappers and chaplains fall into the same category. Many stretcher-bearers and ambulance drivers considered bearing arms unconscionable, yet embraced front line duty in the vital support services. The accounts of fellowship, of men risking their own lives to help others, are as moving as those in which the warrior spirit is to the fore. Men such as Frederick Hall, who ventured into no man’s land on just such a mercy mission at 2nd Ypres. Neither he nor the man whose cries he answered made it back. If Hall’s mission had at least a chance of success, the same couldn’t be said of William Hackett. He was a tunneller who chose to remain with an injured comrade when a roof fall was imminent. The only point to his sacrifice was that it spared the other man a solitary end.

The poignancy of Hackett’s story, and many like it, is matched by accounts of what befell many VC winners in later life. High achievement in the military sphere all too often was not replicated on civvy street. Many resorted to selling their bronze, beribboned mark of distinction. Collectors may have claimed the physical token, but their names and deeds remain inviolable.

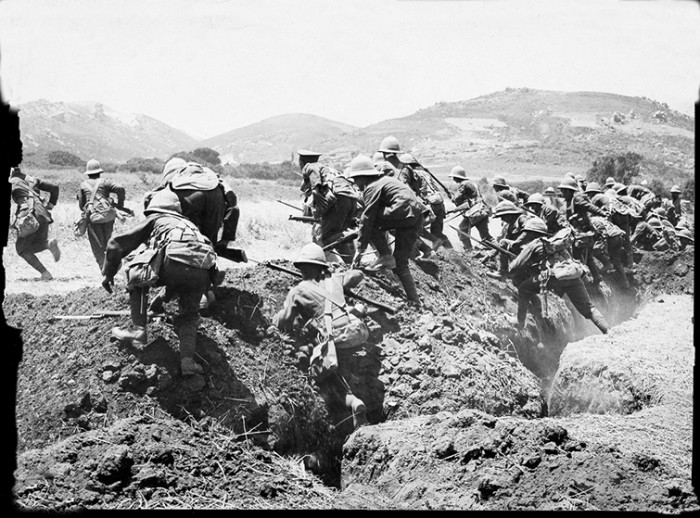

This book is an exhaustive record of the feats and lives of 627 extraordinary men. Whether in detailed accounts or brief sketches, the coverage is comprehensive. In some cases one individual is the focus of attention, while group entries feature men bound together, either by joint enterprise or common theme. Over 1,500 rare and unseen photographs, from the archives of Associated Newspapers, make vivid a momentous period in world history, and its aftermath for the heroic survivors. A chronological account of the conflict, including contemporaneous reports, cuttings and maps, gives context to these remarkable personal histories.The war’s progress is charted, not through politicians’ or strategists’ eyes, but through the efforts of those whose fearless disregard of self made them immortal.

Speaking at a gathering of Victoria Cross winners a decade after the Armistice, the Prince of Wales – the future Edward VIII – referred to them as “a select corps”. It was a body, he went on, “recruited from that very limited circle of men who see what is needed to be done, and do it at once at their own peril”. This book pays homage to 627 members of that select corps.

Meet the heroes:

William Charles Fuller, (Lance Corporal) 13 March 1884 – 29 December 1974

Welsh Regiment, Chivy-sur-Aisne, France, 14 September 1914

During the Battle of the Aisne, Lance Corporal Fuller performed an act of “conspicuous gallantry” that would make him the first Welshman of the Great War to be awarded the Victoria Cross. On 14 September 1914 near Chivy-sur-Aisne, France, Fuller braved very heavy German rifle and machine-gunfire to rescue his mortally wounded commanding officer in the field and take him to a place of relative safety. Captain Mark Haggard had fallen wounded when attempting to charge an enemy machine- gun. He ordered Fuller to retreat but instead the Lance Corporal carried Haggard approximately 100 yards back to the lines where he dressed the officer’s wounds. At Captain Haggard’s request Lance Corporal Fuller ran back to where he’d fallen to retrieve his rifle thus saving it from the enemy’s hands. With the help of two others, Haggard was then carried further back to the safety of a First-Aid dressing station. Fuller stayed with the Captain until the officer died later that evening, then he looked after two other wounded officers. When the dressing station came under heavy enemy fire it was evacuated and later razed to the ground with German shell-fire.

A few weeks later, on 29 October, Lance Corporal Fuller sustained serious injuries after stopping to dress the wounds of a fallen comrade. He was evacuated from France and sent home for surgery, after which he was invalided out of the Army due to the severity of his wounds. For the rest of the war he became a successful recruiting Sergeant in his native Wales. He held the Royal Humane Society Medal for Life-Saving, having dived into the sea in 1935 to rescue two children trapped on a sandbank.

William Fuller was invested with his Victoria Cross by King GeorgeV at Buckingham Palace on the 13 January 1915. He died at the age of 90 in Swansea and was buried at nearby Oystermouth Cemetery. In 2005 his previously unmarked grave was afforded a headstone in memory of his brave acts.

Arthur Martin-Leake, (Surgeon Captain Lieutenant), 4 April 1874 – 22 June 1953

South African Constabulary Royal Army Medical Corps, Zonnebeke, Belgium, 8th November 1914

In over 150 years only three men have received a bar to their Victoria Cross, an indication that if winning the award once is a mark of distinction, to do so twice is a sign of a rare breed indeed. Noel Chavasse gained his double for gallantry in successive years in World War One. New Zealander Charles Upham matched that achievement in the Second World War. The other member of the trio stands out, not just for being the first to break such ground – his bar pre-dates Chavasse’s – but because he stands alone in being honoured for action in two different wars over a decade apart.

Arthur Martin-Leake was born near Ware, Hertfordshire, on 4 April 1874. He attended Westminster School before studying medicine at University College Hospital, qualifying in 1898. He worked briefly at Hemel Hempstead District Hospital until the Boer War took him to the battlefield for the first time. It was while serving as a surgeon- captain with the South African Constabulary that he won his first Cross. On 8 February 1902 Martin-Leake braved a shell-storm to treat two wounded men who had fallen in open ground during heavy fighting at Vlakfontein. He took three bullets himself in what was described as “murderous fire”, yet refused so much as a sip of water until the needs of the two had been met.

By the time World War One erupted, he had added Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons to his name and was working in India as chief medical officer with the Bengal-Nagpur Railway. He had also turned 40; no one was about to come knocking on his door demanding or imploring that he serve once more. Service was in the blood, however.Two years earlier, he had headed back to Europe as part of the

Red Cross contingent saving lives in the Balkan War. In 1914 he was more concerned that he might be considered too old to volunteer, but that didn’t stop him getting dispensation to leave his post in India and presenting himself for duty in Paris, which offered an easier enlistment path. He joined the Royal Army Medical Corps as a lieutenant and was soon plying his trade with the 5th Field Ambulance.The action that brought his secondVictoria Cross came within a matter of weeks. As the First Battle of Ypres raged, Martin-Leake was displaying his customary zeal in trying to aid others, at enormous personal risk. The VC citation highlighted the period spanning 29 October – 3 November 1914, when he was called into action during ferocious fighting near Zonnebeke, a Belgian town lying in the heart of theYpres Salient.Those he attended were lying perilously near the enemy line.The bullets flew thick and fast; at any moment he himself could have joined the injured, or worse. His commanding officer made it clear in his recommendation that this was no uncommon act of valour on Martin-Leake’s part, noting: “It is not possible to quote any one specific act performed because his gallant conduct was continual.” King George V presented Martin-Leake with his historic second VC at Windsor Castle on 24 July 1915, thirteen years after the monarch’s father, Edward VII, had presided over the same ceremony at Buckingham Palace. His own profession also honoured him, the British Medical Association conferring its prestigious Gold Medal, given to those “who shall have conspicuously raised the character of the medical profession”.

He had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel by the end of hostilities, when he returned to India and his pre-war post, which he held – with notable interruptions – for over 30 years. He had retired to the county of his birth by the time the Second World War broke out. Ever ready to do his bit even in his 60s, Martin-Leake commanded an Air Raid Precaution unit. He died in 1953, aged 79. His VC and Bar are held at the Army Medical Services Museum in Surrey.

Frederick William Holmes, (Lance Corporal), 15 September 1889 – 22 October 1969

King’s Own (Yorkshire Light Infantry), Le Cateau, France, 26th August 1914

Frederick Holmes was among the earliest VC winners of the Great War. Serving as a lance corporal in the 2nd Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, he was part of the British Expeditionary Force that found itself on the back foot in the face of overwhelming German numbers in the last days of August 1914. During the retreat from Mons, General Smith-Dorrien elected to stand and fight at Le Cateau, and it was in the thick of this crucial delaying action, on the 26th, that Holmes covered himself in glory. Under heavy fire he carried a badly wounded comrade for two miles before delivering him into the care of stretcher-bearers. He then returned to the fray and saved an unattended 18-pounder from falling into enemy hands by driving the team of horses to the safety of the Allied line.

Bermondsey rolled out the red carpet for its local hero in January 1915, after the investiture ceremony. Frederick Holmes survived the war, emigrating to Australia in later years, where he died at the age of 80. In 2003 his VC medal was bought at auction by a private collector for £92,000.

Victoria Cross Heroes of World War One is published by Atlantic Publishing, £40