Mystical moors: Discover Dartmoor National Park

Escape from the real world among the wild heaths and granite tors of Dartmoor National Park, a poetic and rather mythical destination as Jenny Rowe discovers

“The moor’s swollen waterbelly. Swags and quivers, ready to burst at a step,” wrote Sylvia Plath’s husband and British poet laureate, Ted Hughes in his 1983 work Snipe. Although born in Yorkshire in 1930, Hughes lived in North Tawton, just north of the Dartmoor National Park, for almost four decades. It is very likely that these words were conceived on a particularly soggy day on the moor, perhaps as he strode towards his favourite spot where the rivers Taw, Dart, East Okement and Teign bubble from the ground in the northern “wild quarter” of the National Park. Today an engraved stone is placed here in his memory.

Fittingly, the memorial is made from granite, the stone which characterises this part of Devon. An impermeable rock, it forms a basin here, catching every drop of the region’s high rainfall and resulting in the heavily water-logged ground so eloquently described by Hughes. These areas of blanket bog lie alongside drier expanses of upland heathland, where heather and gorse thrive, staining the ground purple and yellow in summer. Jutting out from this colourful patchwork are more than 150 rocky outcrops. Known as tors, some are stumbled upon (quite literally) or passed without a second thought. But others are so impressive in size, like Vixen Tor, or intriguing in shape, like Bowerman’s Nose, that they have acquired mythical status.

The latter is a prominent granite stack situated near the village of Manaton, which resembles the side profile of a hatted human figure – hence the nose of the name. This eerie coincidence is accounted for locally by the story of Bowerman the Hunter and his hounds who, having disturbed a group of witches on the Sabbath, were led on a wild goose chase across the moors until, when almost crippled by exhaustion, the witches turned him to stone. On a misty or moonless night, you may hear Bowerman and his pack chasing their quarry.

Supernatural tales like this abound on the evocative moors, a place where proper exploration requires that you must relinquish your grip on civilisation – cafés, toilets, A-roads, even roads in general – and perhaps reality itself. The steep-sided Lydford Gorge on the western edge of the National Park is likewise laced with legend. At its northern end is Devil’s Cauldron, an inky, pot-like plunge pool where the River Lyd seethes after a typical Dartmoor downpour. At the southern end of the gorge, which is the deepest in the southwest, is the White Lady Falls, the tallest natural waterfall in Dartmoor at almost 100 foot. Allegedly a kindly ghost called the White Lady appears when anyone gets into trouble in the water and rescues them.

A visit to the similarly atmospheric ancient woodland at Becky Falls allows visitors to immerse themselves in the wonders of the National Park on well-signed pathways (and there is a café and gift shop too). The falls here are more than 65 feet tall, with several smaller displays along the Becka Brook as it tumbles through the boulder-strewn valley. Attracting tourists since 1903, Becky Falls is a classic Dartmoor destination.

Of course, man’s imprint on Dartmoor runs deeper and far further back in time. Tombs have been discovered that place agricultural communities here as early as 3000 BC. One of the most impressive archaeological finds on Dartmoor is the Merrivale Bronze Age ceremonial complex, which is made up of two prominent double stone rows, a stone circle and numerous burial cairns.

It was the tin, copper, silver-lead and granite industries that led to a marked population boom. Tin extraction is the best known of these, and in 1305 King Edward I’s Stannary Charter named Tavistock, Chagford and Ashburton as Devon’s stannary towns, granting them a monopoly on all tin mining in the county. Trading these natural resources was the impetus behind the 1872 South Devon Railway, now the longest established steam railway in the southwest of England, which carried goods off the moor to Totnes from Ashburton via Buckfastleigh. Visitors can still enjoy the latter part of this journey today. Even now, all the large settlements in the area creep around the National Park’s edges, as close as they dare to the metal and stone treasure kept close to its heart.

This is the magic of Dartmoor. Its awkward terrain has proved a powerful defence against modernity’s shrewd advances and unspoilt, hidden gems are around almost every corner. Take little Lustleigh, often dubbed Dartmoor’s prettiest village, which is only reached by driving along terrifyingly narrow lanes (or on foot) and has preserved its medieval parish church, rectory (now known as the Great Hall), and several charming thatched cottages.

So though at times you may get lost in the turbulent tales and gales of the moor, meeting only a handful of Dartmoor ponies as you go, be assured that you are never far from a relic of culture and community.

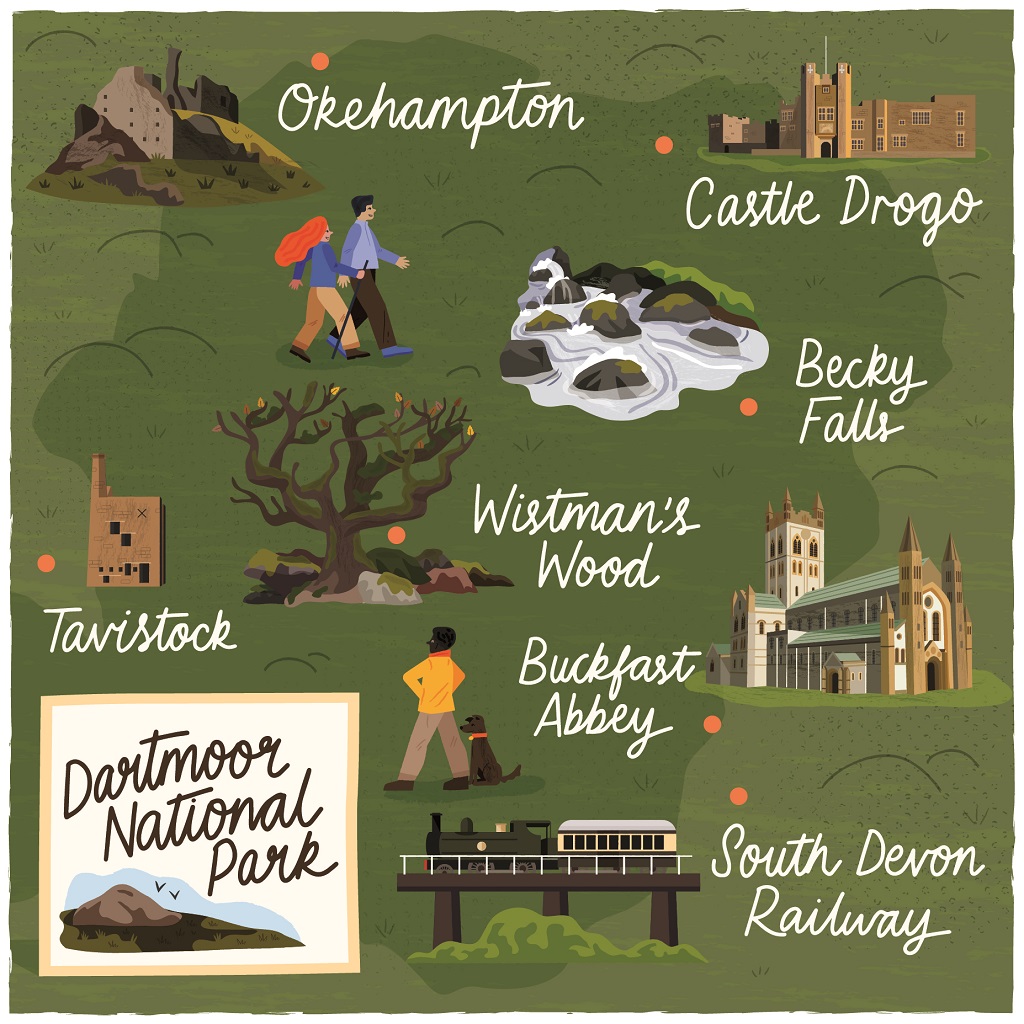

5 things to do on Dartmoor

Okehampton

Known as the “Walking Capital of Devon”, the traditional market town of Okehampton is certainly worth a stop-off on the first and third Saturdays of the month, when the local farmers’ market fills St James’ Chapel Square. From here, walkers can head down the 37-mile West Devon Way, while cyclists should opt for the Granite Way, an 11-mile trail to the Anglo-Saxon town of Lydford.

Don’t go anywhere, though, until you’ve visited the dramatic ruins of Okehampton Castle. Mentioned in the 1086 Domesday Book, it was likely built shortly after the Norman Conquest and is the largest of its kind in the county. Also worth a look is the Museum of Dartmoor Life, which holds a collection spanning 5,000 years focused on local people and industries. www.visitokehampton.co.uk

Buckfast Abbey

Not only is Buckfast Abbey a beauty, it is also the fully functional home to working Benedictine monks. Originally founded by King Canute in 1018, Buckfast was a small and relatively unprosperous monastery. It wasn’t until it became a Cistercian Abbey in 1147 that its fortunes started to look up.

As wealthy landowners, the Cistercians became the country’s main wool producers. The former grange barn still survives a short distance from the Abbey’s North Gate, though it’s been converted for residential use. Responsible for its own guest house, almshouse, school and markets in the 15th century, sadly Henry VIII came knocking during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Monks didn’t return until 1882, but today a visit is in equal parts serene and spectacular. The Lavender Garden is an extra treat in summer. www.buckfast.co.uk

Wistman’s Wood

Walking through this dense tangle of stunted ancient oak woodland you might feel as if you’ve stepped into a fairytale, on the brink of enchantment by a waggish wizard or else ambush by a touchy troll. Gnarled branches sprawl between granite boulders, and all are dressed from top to toe in an emerald green fur of moss and lichen. It’s unsurprising that many say it is the most haunted place on Dartmoor.

The name of Wistman’s Wood, which could derive from “wise man’s wood” or the dialect word wisht meaning “eerie”, also refers to the surrounding Nature Reserve, which covers 420 acres and incorporates beautiful, panoramic views of wild Devon. It’s also a great spot for watching woodpecker and buzzard. www.dartmoor.gov.uk

Tavistock

As well as a producer of wool, the market town of Tavistock played a key role in another important local industry: metal mining. This led to its inclusion in the West Devon and East Cornwall Mining Landscape UNESCO World Heritage Site. Copper was generally dug from the Tamar valley to the west, while tin poured off Dartmoor into the town, which was named one of Devon’s three original stannary towns in 1305.

The money brought in from the mines allowed the 7th Duke of Bedford to remodel much of the medieval town in the mid-19th century, creating many of the elegant public buildings found in the centre today, as well as the miners’ homes, also known as the Bedford Cottages. www.visit-tavistock.co.uk

Castle Drogo

One of the first 20th-century buildings taken on by the National Trust, Castle Drogo was acquired in 1974, largely because it had been designed by one of England’s greatest architects, Sir Edwin Lutyens. The granite fortress perched above the Teign Gorge and on the northern border of the National Park was originally built for self-made millionaire Julius Drewe (so rich he was able to retire at 33) between 1910 and 1930. It is often referred to as England’s last castle by historians and was once upon a time one of the region’s most popular National Trust properties.

Though the castle itself is currently undergoing major conservation work, it remains a must-visit both for the views from neighbouring Piddledown Common over the gorge and National Park, and the Lutyens-designed gardens, which were literally carved out of granite. An enchanting haven in all seasons, summer and autumn may be most impressive, with vast herbaceous borders that to this day reflect the plans made by renowned plantsman George Dillistone in the 1920s. www.nationaltrust.org.uk/castle-drogo