Aberglasney Gardens

Graham Rankin

Aberglasney Gardens is situated in the fertile Tywi Valley on the western fringes of the Brecon Beacons in Wales – an area of great historical interest, surrounded by lush green valleys, mountain wilderness and the remains of ancient castles. Before I discovered this wonderful site I would have travelled along the A40 countless times unknowingly passing Aberglasney en route to Pembrokeshire.

I had never really explored the county of Carmarthenshire and was struck by its immense beauty. It transpired that very few people knew that Aberglasney was here. I first became aware of the site when a long-forgotten historic garden feature was rediscovered near the old mansion – a structure so important that it inspired an unprecedented restoration campaign, as well as a colossal amount of research, discussion and argument.

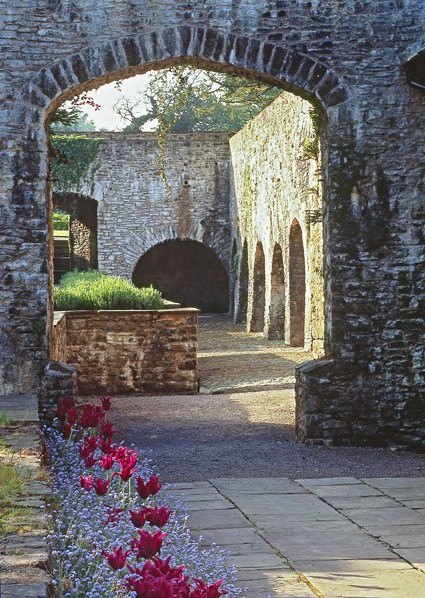

The root cause of all this interest was a courtyard surrounded by rows of arches creating a raised walkway – all but unrecognizable in its state of decay; it was an architectural conundrum. Garden historians had many conflicting views as to its origin and purpose and years of deliberation ensued. Maybe it was sheer disbelief that was to blame for the long-drawn-out scepticism voiced by academics of garden history.

Eventually after much fundraising and the invaluable financial assistance of an American benefactor, site clearance, archaeological research and building restoration started in 1998. Soon the structures’ true architectural form was made visible; it turned out to be a Cloister Range and Parapet Walk, a rare piece of Renaissance architecture, unique in the British Isles and with very few examples remaining in other parts of Europe.

The gravity-defying remains of the adjoining stone walls were bound together by dense masses of ivy. The once well-cultivated gardens were swamped with rampant invasive vegetation. An upper storey of self-sown ash and sycamore trees populated the grounds and specimens grew out of every conceivable crevice in the buildings’ masonry. It is understandable why it was considered by most, quite literally beyond restoration.

A vast project of clearance, evaluation and rebuilding began. Early on a team from BBC Wales began recording the process on film. The series of programmes broadcast in 1999, just as the garden was being opened to the public, was entitled Aberglasney: A Garden Lost in Time. The name echoed the ‘Lost Gardens of Heligan’, the Cornish project that virtually launched the trend for rediscovering and reviving forgotten gardens a few years earlier. It would perhaps to be more accurate to say the garden at Aberglasney was found just in time for restoration to save it. People were fascinated by the unfolding of the story, and the publicity generated put Aberglasney on the map.

The initial phase of structural restoration was being undertaken when I arrived on the scene in the spring of 1999. It was not a case of creating a garden, but getting the grounds suitable for people to walk around in safety and a degree of comfort. When Aberglasney opened, there was hardly a garden to be seen. Apart from very new planting in two walled gardens, endless walls, a basic path network and acres of brown earth was all that was evident. The majority of visitors who made a visit in the early days were fascinated with what they saw – a rare opportunity not only to see a garden being created from a blank canvas, but a house being brought back to life. The archaeologists were still at work unearthing new discoveries to reveal Aberglasney’s long history on a daily basis, including silver coins dating back to the 13th century.

Taking on the task of creating a garden at Aberglasney was going to be a huge long-term commitment and a challenge of a lifetime, in fact I initially turned the position down as it was such a daunting project. Having always worked with mature gardens, the acres of horticultural barrenness was not particularly enticing, however, the clinching deal was that I would have a free hand in the design and planting of the gardens and, given the assurance of adequate funding, I decided to quite literally ‘grasp the nettle’.

Unlike some historic gardens, I was adamant that Aberglasney should not be stuck in a time warp, although the exception to this philosophy was the design of the Cloister Garden. While the hard landscaping of the Cloister Garden was dictated by archaeological research, there was no evidence of the style of garden that would have originally been planted. The reinstatement of the garden within the cloistered area was meticulously researched. Many hours were spent looking through books on garden history to see what style of garden would have been typical during the early part of the 17th century in order to create an accurate historical representation.

The Dutch polymath Hans Vredeman de Vries designed hundreds of symmetrical grass parterres, illustrated in his book Hortorum Viridariorumque Formae, published in 1583. It hugely influenced the style of garden design during the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean period. Another valuable source was a modern book, The Artist and the Garden, by Roy Strong. This illustrates many paintings of the period, often portraits in which a garden is seen incidentally in the background. Two paintings from Roy Strong’s book influenced the design. The first was a beautiful study of a lady of the Byng family, who lived in Kent, dating from about 1620. The other painting was a portrait of Sir William Style of Langley, which hangs in the Tate Gallery showing a cloistered garden with a formal grassed parterre known as an ‘enamelled mead’, with ‘pinpricks’ of flower colour within the grassed area.

The rest of the garden area now covers an area of about 10 acres and its planting does not reflect the garden’s antiquity, but is decidedly eclectic with many diverse areas. The development of the garden will continue to showcase the very best varieties and new plant introductions as plant collectors discover new and exciting species.

If I had to choose one area of the garden that has given me more pleasure to create than anywhere else it would have to be the ‘Ninfarium’. The idea of glazing over and planting the ruinous inner courtyard of the mansion and the derelict south wing was conceived soon after I started work at Aberglasney. The covered garden would also give me a chance to grow a wide range of tender plants increasing the diversity to be admired.

The project was completed to much acclaim in August 2005, but the new garden area needed a name. Several ideas came to mind, such as the Atrium Garden and the Courtyard Garden, both of which I suppose would have been adequate. However, the area was reminiscent of the stunning romantic gardens of Ninfa, which was built at the foot of the Lepini Mountains 45 miles southeast of Rome.

The word ‘Ninfa’ came from a small Roman temple that once stood where the river Nympheus entered the garden and, in Roman times, was dedicated to nymph goddesses. Ninfa was once a prosperous town supporting seven churches and all contained within a double walled fortification. Its prosperity lasted for 600 years, from the eighth century until it was destroyed by the inhabitants of hostile neighbouring towns in 1381. Having chosen to pay tribute to Ninfa, the suffix ‘arium’ was added which usually denotes a certain place. In 2006 the Ninfarium won a national award for the Best Garden/Design project in the UK.

After the Ninfarium, Bishop Rudd’s Walk with its rare orchids and woodland treasures would come a close second; however the spring colour in the Asiatic Garden and the diminutive plants grown in the Alpinum would also be strong contenders.

The mansion itself has its origins in the 15th century, but most of what can be seen today is much later, late Georgian to early Victorian.

Aberglasney Gardens, Llangathen, Carmarthenshire SA32 8QH

For more details call 01558 668 998 or visit www.aberglasney.org