Explore Cornwall’s Stately Homes

In stark contrast to the humble cottages in Cornwall’s villages, the county’s grand stately houses stand as reminders of the power and wealth of its most influential families

Words: Vicky Sartain

Lanhydrock, Bodmin

From its ornate 17th-century gatehouse, to its sweeping drive leading to the imposing grey granite manor house, Lanhydrock cuts a dash from every angle and was the pride of its original owner, politician John Robartes. His wealth was thanks to his grandfather’s work in the local tin industry, which was inherited in turn by his father Richard, who was once described as being the ‘wealthiest in the west’. John was determined to develop a more imposing residence than his forebears and from 1634-51 the original manor was substantially altered, with four ranges built around a central courtyard. The estate did not hold John’s attention for long however, and in 1660, having found favour with the newly-restored monarch, Charles II, he spent the majority of his time in London while Lanhydrock was left to decline. A limited interest in the fate of the estate contributed to its further demise as various heirs set about depleting the family fortune. Towards the end of the 18th century, having passed to a different branch of the family owing to the lack of a direct male inheritor, the neglected property was reduced in size and, in keeping with timely trends for red brick, the exterior walls were painted red.

Much of the present building was reconstructed significantly by Anna Maria Agar who inherited it in 1798, and then again by her successive grandson Thomas 2nd Lord Robartes following a devastating fire in 1881. According to his father’s wishes, Thomas rebuilt the house as it was prior to the fire, while its interiors were refashioned in the High Victorian style, incorporating a labyrinth of servants’ quarters, attic bedrooms and family rooms, including a billiard room, smoking room, ladies’ boudoir and drawing room. Neither gas nor electricity was installed due to Thomas’s fear of fire, and ceilings were created of fireproof reinforced concrete. Just one ceiling survived the 1881 blaze – the 35-metre-long barrel vaulted plasterwork of the Long Gallery – which is still arguably the most spectacular feature of the house. Its carved friezes depict bible stories, including Noah’s Ark, which were a helpful resource for improving the children’s religious education – values important to the Puritan master of the house. Events in the 20th century would change Lanhydrock for ever, when the two world wars left its future in the balance. Salvation came from the National Trust, who assumed responsibility for the estate in 1953, and their efforts since have helped to attract some 200,000 visitors through the house’s doors every year, reawakening the property from its long slumber. Features to look out for during a visit include the grand family reception rooms, light and airy nurseries, elegant bedrooms and generous servants’ quarters. Outside, the garden is famous for spectacular magnolias, camellias and rhododendrons complementing the profusion of wild flowers.

Cotehele, St Dominick, near Saltash

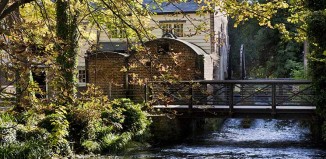

Tucked away in a steep valley on the west bank of the River Tamar, Cotehele is a Tudor treasure trove, steeped in stories and adorned with a collection of tapestries, armour, weaponry, pewter, brass and old oak furniture. It was first established as a grand family residence in 1485 by Sir Richard Edgcumbe, whose distinguished ancestors had been owners of the wider Cotehele estate since 1353. After proving himself at the Battle of Bosworth, Sir Richard had been handsomely rewarded by Henry Tudor, and dedicated the last four years of his life to developing a suitably impressive home – a project that was continued in earnest by his son Piers.

The family’s new-found wealth would carry to future generations, even funding the building of Mount Edgcumbe House – a substantial 16th-century property overlooking Plymouth Sound. This would later become the principal family seat in preference over Cotehele, which could never be close enough to the city’s fashionable society. For a long period in the early 19th century, however, Cotehele was something of a novelty for owner George, 1st Earl of Mount Edgcumbe to entertain his guests. As a member of the Society of Antiquities he understood the importance of preserving the interiors, although little of the original Tudor furnishings now remain. Visitors were met with an attractively rustic courtyard featuring archways and cobbled passageways watched through gabled windows in golden stonework. The Hall provided the modest reception area, with its rough lime ash floor and plain, lime-washed walls, coloured by the light streaming through a striking stained glass window, featuring the Edgcumbe coat of arms and those of the distinguished local families that the Edgcumbes wed into.

Further into the house are 18th-century Flemish tapestries, a mix of 17th and 18th-century furniture and brightly decorated soft furnishings and upholstery embellished with crewelwork patterns. Vibrancy contrasts against tawny wood fixtures and fittings – the Red Room offering a sensory experience from its pine floorboards to cherubic tapestries, red wool bed curtains and age worn ceiling. Possibly the most romantically evocative area is the King Charles’s Room, named in honour of the doomed monarch who is thought to have slept here in 1644 en route to Exeter.

This lovely home fell into ruin in the 18th century until it was rescued by the National Trust in 1947. Today, its granite stonework is fringed with seasonal blooms in a garden famous in its own right, rolling down to the River Tamar. Completing the setting is a 19th-century sailing barge, Shamrock, which is moored at Cotehele quay. While here, visitors can learn more about the Tamar Valley at the National Trust’s Discovery Centre.

Antony House, Torpoint

Until Hollywood film director Tim Burton decided to use Antony as a location in the 2010 film Alice in Wonderland, this early 18th-century mansion set in parkland and sweeping, Humphry Repton landscaped gardens on the Cornwall/Devon border had pretty much kept itself to itself. However, its moment in the spotlight saw visitor numbers soar as people queued to follow in the footsteps of the film’s stellar cast and discover the story of its fairytale setting. The Carew family has lived at Antony since the 15th century, with the latest generation still in residence today, albeit in a much grander building created by Sir William Carew in 1720. Having amassed great wealth through inheritance and marriage, Sir William created a classical house in grey Pentewan stone in a setting of sweeping meadows and big skies. Portraits of various family members across the generations decorate the walls and the interiors of rich, stained oak panelling in the principal ground floor rooms lend an air of importance, particularly in the Hall and Saloon, where the windows look over the garden to the River Lynher estuary. One painting worth looking out for is Edward Bower’s striking portrait of Charles I at his trial.

As its name might suggest, The Tapestry Room is festooned with a number of 17th and 18th-century textiles, complemented by furnishings of the same period. While here it is worth paying attention to the finer detail, such as the carvings on table legs, the collections of miniatures and the unusual Chinese military figures stacked above the mantelpiece. Only part of the house is open to the public in respect of the present Carew family, but even in the aforementioned public rooms visitors will get the sense that the property functions as a well-loved home. The present baronet, Sir Richard Carew Pole, is keen to keep traditions alive, commissioning portraits of current family members and refreshing the grounds with sculptures.

For many of today’s visitors it is the gardens, in which scenes of the Mad Hatter’s tea party were filmed, that are the biggest draw. Home to the National Collection of Daylilies, and a woodland garden filled with rhododendron, azalea, magnolia and camellia, the grounds were magical long before being attributed to Alice’s travels. Offering beautiful river views, garden walks are framed by conical yew topiary and high box hedges all of which appealed to Tim Burton who considered this perfect for a mischievous white rabbit – a setting made all the more bewitching when the river mist rolls in. Symmetry in the gardens reflects that of the house itself, including across the knot garden’s woven shrubbery, while yards away any residual formality meets rebellious unkempt borders. Make the best of the grounds by following the sculpture trail or, like Alice, go forth in blind curiosity.

Prideaux Place, Padstow

It may be one of the Westcountry’s oldest properties, but this largely Elizabethan mansion overlooking the picturesque fishing harbour of Padstow in North Cornwall is still very much a family home, albeit one adorned with exquisite ancestral treasures. Fourteen generations of the Prideaux family have resided here since Sir Nicholas bought the land and built the house in 1592, and visitors today may even bump into a member of the family as they make their way through the corridors and rooms filled with collections of fine furniture, porcelain and art.

The interiors combine original Elizabethan architecture and 18th-century gothic style, inspired by the famous former home of antiquarian Horace Walpole at Strawberry Hill in Twickenham. The dark fairytale whimsy that shaped Walpole’s residence was recreated in Prideaux’s turrets and battlements, while its interiors were designed to emulate a medieval ambience. As with many large estates in the region, Prideaux Place was given up for the Second World War effort, when the soldiers from the American army were stationed at the house in preparation for the D-Day landings in 1944. Of Prideaux’s 81 rooms, 46 are bedrooms, but the majority are now uninhabitable, their last occupants being the soldiers who briefly dwelled there.