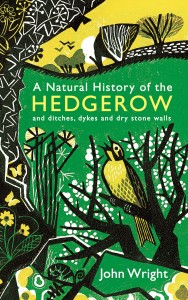

A Natural History of the Hedgerow

At this time of year British hedgerows spring to life. In an excerpt from his new book, A Natural History of the Hedgerow, forager and naturalist John Wright introduces his subject matter and explains why hedgerows are so important…

I spend a large proportion of my time wandering along hedgerows, examining walls and banks and clambering in and out of ditches. Even a drive along a country road or – more dangerously still – a motorway, will have me glancing out of the window to see what is growing by the wayside.

A favourite game in my family is to count how many cherry plum trees we can spot on a trip from our home in Dorset to, say, Oxford (147), though it could just as well be wild parsley stands or apple trees we are counting. Lethal as these distractions may be, at least they do not slow me down, but a walk from one end of 100-metre hedge to the other can take me half an hour and any companions soon get bored and walk on ahead. “But aren’t you interested?” I might ask rather pompously. “Look at this elder tree that’s had its bark rubbed away by a deer,” or “Here’s an oak apple, let’s see if the wasp has flown,” or “This plant will have you dead in half an hour if you eat it,” and so on.

What interests me most are the mysteries – plants I do not recognise at all, fungi that I can put a genus to but not a species, things that could be animal, vegetable or mineral. I would like to think that such an attitude is not unusual; after all, many of my friends are enthusiastic naturalists of one sort or another, but, sadly, I do not think that this is the case.

I often take people on mushroom and hedgerow forays and while a few can tell an elder from an alder they are in the minority. The people who join me do so to learn about wild foods; what can be found in hedgerow, wood, pasture and meadow that tastes pleasant, won’t have them in A&E and are free. I duly oblige, but I try to show them more – much more. I think that, on the whole, I am successful, though it is not always easy to tell. On a few occasions my success has been immediate and obvious. I am proud of what I do, though I take no great credit for it; it is just the everyday delight of an enthusiast, sharing the objects of his passion with others. I just slow people down and invite them to look.

For those who are willing to go slow, there is much to see; much more than might be imagined. Part III of the book, the largest part, covers the natural history of Britain’s hedges in some detail. It tells the stories of hawthorn and blackthorn, of oak and elm and a dozen more hedgerow trees, but also of those organisms that depend on them or cohabit with them. Some are obvious, like the endless stands of cow parsley that appear every spring, others are very much more subtle. The hawthorn, for example, supports dozens of microfungi, many micromoths and macromoths, several galls and scores of other organisms.

This is what makes a walk along a hedgerow so much more than just a bit of exercise or a breath of fresh air. My particular interest is largely in hedgerow trees and plants and what may be called their “diseases” and symbionts – organisms living in symbiosis. This may disappoint those with an interest in vertebrates, be they bird, bat or badger. I do, however, write of the relationships these animals have with their hedgerow habitat. Reptiles and amphibians barely get a mention except to acknowledge that they too can find a home in a hedge or wall.

Quite how unique hedges are to Britain is not sufficiently appreciated. For example, the “tunnels” sometimes formed by roadside hedges, notably in the south, are almost unknown in other parts of the world. I am fortunate in that where I live I can see half a dozen hedges just by glancing out of my office window at the hill above my village. Most people in Britain live in towns and may not see a rural hedge at close quarters from one year to the next (I was a townie once, so I mean no criticism).

Those fabled visitors arriving from outer space would have, literally, a very different view. From the air the landscape is dominated not by towns and cities, not by roads and factories, not even by forest or bare heath, but by a coast-to-coast network of hedges and fields. They might assume that the entire population spent its time creating and tending this truly vast construction. Not so long ago, they would have been right.

Once a year or more, many of us become like those aliens for a few minutes. Returning from a holiday in Greece or Turkey or anywhere else, we see what they would see and it takes our breath away. Beautiful as our holiday destinations may be, they cannot compare to the lush, green patchwork visible beneath us as we take the descent to Gatwick, Heathrow or – my personal favourite – Exeter in Devon.

What, these extra-terrestrial visitors might wonder, are all those lengths of hedges for? Religious observance? Installation art? Some among those who live on this island often wonder too. The answer is that there is no single use for a hedge, but many. The answer is that there is no single use for a hedge, but many. It may simply be a way of controlling and sheltering stock; a means of protecting crops and stock from unwelcome animals or from theft; as a defence against soil erosion, or as a resource for timber, food and medicine. These are practical matters, but there are also more psychological and social issues, such as the demarcation of private property and privacy. Which of these are important at any one time – and it may be several of them – determine the fate and nature of the hedge.

What, these extra-terrestrial visitors might wonder, are all those lengths of hedges for? Religious observance? Installation art? Some among those who live on this island often wonder too…

If a hedge ceases to be valued, then the land it is on is usually reclaimed and put to better use. For a thousand years hedgerows were almost entirely dispensed with in about half of England and Wales, after which they were widely replanted only, more recently, to be dispensed with all over again in many parts of the country.

To the list of hedge use we must also add one further consideration. Before the advent of intensive agriculture, hedgerow natural history was not specially valued. The large tracts of land that had been more or less left to nature made it an also-ran in the natural history stakes. Now that our wildlife habitats have been so drastically reduced, hedgerows lead the field. While few of the agricultural reasons for planting or retaining hedgerows remain that relevant today, their importance as a natural history habitat cannot be overstated.

Today hedgerow loss is understood by most people to be a bad thing and hedges are protected as never before. Unfortunately, many of those remaining are in a poor state of repair. Having outlived their usefulness – large arable farms need no hedges – they have been left to wither. Pastoral farming, for which hedges are certainly useful, often make do with barbed wire. Even when a hedge exists, barbed wire is often used as the primary physical barrier and the hedge left to do its best, or its worst.

Some effort is being made to address these problems, but we must face the fact that many hedges are doomed in the long term. Those that survive, however, must be cared for with informed and sensitive cutting and repairing regimes. If a hedge flourishes, then the organisms that depend on it will do well. It is neither particularly onerous nor expensive to look after hedges and it often involves not doing something (such as verge cutting) – or at least doing it at the right time and with a little more thought.

My book is a personal account of the hedgerow because, for me, hedgerows are a personal matter. They are our common heritage and we should delight in them and protect them as though they were our personal property. In one way they truly are our property, as we enjoy historical and statutory rights to their bounty. Hedgerows were once a source of timber, of medicinal herbs and, crucially, of food for ourselves and for animals. Picking blackberries, stinging nettles, hazel nuts or sloes is less of a tradition and more a part of our biological heritage. It is something we are meant to do.

Hedgerows were once a source of timber, of medicinal herbs and, crucially, of food for ourselves and for animals. Picking blackberries, stinging nettles, hazel nuts or sloes is less of a tradition and more a part of our biological heritage. It is something we are meant to do…

In the past, and to some extent the present, the hedgerow was a resource that was essential to life. While the close behind every house grew vegetables and the fields might supply a subsistence quantity of corn and occasional meat, the hedgerow and the waste ground were essential for providing some nutritional variety for the rural population.

In the past, and to some extent the present, the hedgerow was a resource that was essential to life. While the close behind every house grew vegetables and the fields might supply a subsistence quantity of corn and occasional meat, the hedgerow and the waste ground were essential for providing some nutritional variety for the rural population.

A piece in Jackson’s Oxford Journal of 1778 gives a hint of the value of this free source of food: “The present is the greatest Nut Year that has been known for a long Time past; the Hazels are every where bending beneath the Weight of their Produce, and as it were by their friendly Curves, inviting the Hand of the Rustic to pluck their Clusters.”